- Home

- Anthony Trollope

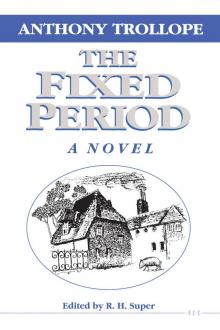

The Fixed Period Page 9

The Fixed Period Read online

Page 9

CHAPTER IX.

THE NEW GOVERNOR.

"So," said I to myself, "because of Jack and his love, all theaspirations of my life are to be crushed! The whole dream of myexistence, which has come so near to the fruition of a waking moment,is to be violently dispelled because my own son and Sir KenningtonOval have settled between them that a pretty girl is to have her ownway." As I thought of it, there seemed to be a monstrous crueltyand potency in Fortune, which she never could have been allowed toexercise in a world which was not altogether given over to injustice.It was for that that I wept. I wept to think that a spirit of honestyshould as yet have prevailed so little in the world. Here, in ourwaters, was lying a terrible engine of British power, sent out by aBritish Cabinet Minister,--the so-called Minister of Benevolence, bya bitter chance,--at the instance of that Minister's nephew, to putdown by brute force the most absolutely benevolent project for thegovernance of the world which the mind of man had ever projected. Itwas in that that lay the agony of the blow.

I remained there alone for many hours, but I must acknowledgethat before I left the chambers I had gradually brought myself tolook at the matter in another light. Had Eva Crasweller not beengood-looking, had Jack been still at college, had Sir Kennington Ovalremained in England, had Mr Bunnit and the bar-keeper not succeededin stopping my carriage on the hill,--should I have succeeded inarranging for the final departure of my old friend? That was thequestion which I ought to ask myself. And even had I succeeded incarrying my success so far as that, should I not have appeared amurderer to my fellow-citizens had not his departure been followed inregular sequence by that of all others till it had come to my turn?Had Crasweller departed, and had the system then been stopped, shouldI not have appeared a murderer even to myself? And what hope hadthere been, what reasonable expectation, that the system should havebeen allowed fair-play?

It must be understood that I, I myself, have never for a momentswerved. But though I have been strong enough to originate the idea,I have not been strong enough to bear the terrible harshness of theopinions of those around me when I should have exercised againstthose dear to me the mandates of the new law. If I could, in thespirit, have leaped over a space of thirty years and been myselfdeposited in due order, I could see that my memory would havebeen embalmed with those who had done great things for theirfellow-citizens. Columbus, and Galileo, and Newton, and Harvey, andWilberforce, and Cobden, and that great Banting who has preserved usall so completely from the horrors of obesity, would not have beennamed with honour more resplendent than that paid to the name ofNeverbend. Such had been my ambition, such had been my hope. But itis necessary that a whole age should be carried up to some proximityto the reformer before there is a space sufficiently large for hisoperations. Had the telegraph been invented in the days of ancientRome, would the Romans have accepted it, or have stoned Wheatstone?So thinking, I resolved that I was before my age, and that I must paythe allotted penalty.

On arriving at home at my own residence, I found that our _salon_ wasfilled with a brilliant company. We did not usually use the room;but on entering the house I heard the clatter of conversation, andwent in. There was Captain Battleax seated there, beautiful with acocked-hat, and an epaulet, and gold braid. He rose to meet me, andI saw that he was a handsome tall man about forty, with a determinedface and a winning smile. "Mr President," said he, "I am in commandof her Majesty's gunboat, the John Bright, and I have come to pay myrespects to the ladies."

"I am sure the ladies have great pleasure in seeing you." I lookedround the room, and there, with other of our fair citizens, I sawEva. As I spoke I made him a gracious bow, and I think I showedhim by my mode of address that I did not bear any grudge as to myindividual self.

"I have come to your shores, Mr President, with the purpose of seeinghow things are progressing in this distant quarter of the world."

"Things were progressing, Captain Battleax, pretty well before thismorning. We have our little struggles here as elsewhere, and allthings cannot be done by rose-water. But, on the whole, we are aprosperous and well-satisfied people."

"We are quite satisfied now, Captain Battleax," said my wife.

"Quite satisfied," said Eva.

"I am sure we are all delighted to hear the ladies speak in sopleasant a manner," said First-Lieutenant Crosstrees, an officer withwhom I have since become particularly intimate.

Then there was a little pause in the conversation, and I felt myselfbound to say something as to the violent interruption to which I hadthis morning been subjected. And yet that something must be playfulin its nature. I must by no means show in such company as was nowpresent the strong feeling which pervaded my own mind. "You willperceive, Captain Battleax, that there is a little difference ofopinion between us all here as to the ceremony which was to havebeen accomplished this morning. The ladies, in compliance with thatsoftness of heart which is their characteristic, are on one side; andthe men, by whom the world has to be managed, are on the other. Nodoubt, in process of time the ladies will follow--"

"Their masters," said Mrs Neverbend. "No doubt we shall do so whenit is only ourselves that we have to sacrifice, but never when thequestion concerns our husbands, our fathers, and our sons."

This was a pretty little speech enough, and received the eagercompliments of the officers of the John Bright. "I did not mean,"said Captain Battleax, "to touch upon public subjects at such amoment as this. I am here only to pay my respects as a messenger fromGreat Britain to Britannula, to congratulate you all on your latevictory at cricket, and to say how loud are the praises bestowedon Mr John Neverbend, junior, for his skill and gallantry. Thepower of his arm is already the subject discussed at all clubs anddrawing-rooms at home. We had received details of the whole affairby water-telegram before the John Bright started. Mrs Neverbend, youmust indeed be proud of your son."

Jack had been standing in the far corner of the room talking to Eva,and was now reduced to silence by his praises.

"Sir Kennington Oval is a very fine player," said my wife.

"And my Lord Marylebone behaves himself quite like a British peer,"said the wife of the Mayor of Gladstonopolis,--a lady whom he hadmarried in England, and who had not moved there in quite the highestcircles.

Then we began to think of the hospitality of the island, and theofficers of the John Bright were asked to dine with us on thefollowing day. I and my wife and son, and the two Craswellers, andthree or four others, agreed to dine on board the ship on the next.To me personally an extreme of courtesy was shown. It seemed asthough I were treated with almost royal honour. This, I felt, waspaid to me as being President of the republic, and I endeavoured tobehave myself with such mingled humility and dignity as might befitthe occasion; but I could not but feel that something was wantingto the simplicity of my ordinary life. My wife, on the spur of themoment, managed to give the gentlemen a very good dinner. Includingthe chaplain and the surgeon, there were twelve of them, and sheasked twelve of the prettiest girls in Gladstonopolis to meet them.This, she said, was true hospitality; and I am not sure that I didnot agree with her. Then there were three or four leading men of thecommunity, with their wives, who were for the most part the fathersand mothers of the young ladies. We sat down thirty-six to dinner;and I think that we showed a great divergence from those usualcolonial banquets, at which the elders are only invited to meetdistinguished guests. The officers were chiefly young men; and agreater babel of voices was, I'll undertake to say, never heard froma banqueting-hall than came from our dinner-table. Eva Crasweller wasthe queen of the evening, and was as joyous, as beautiful, and ashigh-spirited as a queen should ever be. I did once or twice duringthe festivity glance round at old Crasweller. He was quiet, and Imight almost say silent, during the whole evening; but I could seefrom the testimony of his altered countenance how strong is thepassion for life that dwells in the human breast.

"Your promised bride seems to have it all her own way," said CaptainBattleax to Jack, when at last the ladies had withdrawn.

> "Oh yes," said Jack, "and I'm nowhere. But I mean to have my inningsbefore long."

Of what Mrs Neverbend had gone through in providing birds, beasts,and fishes, not to talk of tarts and jellies, for the dinner of thatday, no one but myself can have any idea; but it must be admittedthat she accomplished her task with thorough success. I was told,too, that after the invitations had been written, no milliner inBritannula was allowed to sleep a single moment till half an hourbefore the ladies were assembled in our drawing-room; but theirefforts, too, were conspicuously successful.

On the next day some of us went on board the John Bright for a returndinner; and very pleasant the officers made it. The living on boardthe John Bright is exceedingly good, as I have had occasion to learnfrom many dinners eaten there since that day. I little thought when Isat down at the right hand of Captain Battleax as being the Presidentof the republic, with my wife on his left, I should ever spend morethan a month on board the ship, or write on board it this account ofall my thoughts and all my troubles in regard to the Fixed Period.After dinner Captain Battleax simply proposed my health, paying tome many unmeaning compliments, in which, however, I observed that noreference was made to the special doings of my presidency; and heended by saying, that though he had, as a matter of courtesy, andwith the greatest possible alacrity, proposed my health, he wouldnot call upon me for any reply. And immediately on his sitting down,there got up a gentleman to whom I had not been introduced beforethis day, and gave the health of Mrs Neverbend and the ladies ofBritannula. Now in spite of what the captain said, I undoubtedly hadintended to make a speech. When the President of the republic hashis health drunk, it is, I conceive, his duty to do so. But here thegentleman rose with a rapidity which did at the moment seem to havebeen premeditated. At any rate, my eloquence was altogether stopped.The gentleman was named Sir Ferdinando Brown. He was dressed insimple black, and was clearly not one of the ship's officers; butI could not but suspect at the moment that he was in some specialmeasure concerned in the mission on which the gunboat had been sent.He sat on Mrs Neverbend's left hand, and did seem in some respectto be the chief man on that occasion. However, he proposed MrsNeverbend's health and the ladies, and the captain instantly calledupon the band to play some favourite tune. After that there wasno attempt at speaking. We sat with the officers some little timeafter dinner, and then went ashore. "Sir Ferdinando and I," said thecaptain, as we shook hands with him, "will do ourselves the honour ofcalling on you at the executive chambers to-morrow morning."

I went home to bed with a presentiment of evil running across myheart. A presentiment indeed! How much of evil,--of real accomplishedevil,--had there not occurred to me during the last few days! Everyhope for which I had lived, as I then told myself, had been broughtto sudden extinction by the coming of these men to whom I had been sopleasant, and who, in their turn, had been so pleasant to me! Whatcould I do now but just lay myself down and die? And the death ofwhich I dreamt could not, alas! be that true benumbing death whichwe think may put an end, or at any rate give a change, to all ourthoughts. To die would be as nothing; but to live as the latePresident of the republic who had fixed his aspirations so high,would indeed be very melancholy. As President I had still twoyears to run, but it occurred to me now that I could not possiblyendure those two years of prolonged nominal power. I should be thelaughing-stock of the people; and as such, it would become me to hidemy head. When this captain should have taken himself and his vesselback to England, I would retire to a small farm which I possessed atthe farthest side of the island, and there in seclusion would I endmy days. Mrs Neverbend should come with me, or stay, if it so pleasedher, in Gladstonopolis. Jack would become Eva's happy husband,and would remain amidst the hurried duties of the eager world.Crasweller, the triumphant, would live, and at last die, amidst theflocks and herds of Little Christchurch. I, too, would have a smallherd, a little flock of my own, surrounded by no such glories asthose of Little Christchurch,--owing nothing to wealth, or scenery,or neighbourhood,--and there, till God should take me, I would spendthe evening of my day. Thinking of all this, I went to sleep.

On the next morning Sir Ferdinando Brown and Captain Battleax wereannounced at the executive chambers. I had already been there at mywork for a couple of hours; but Sir Ferdinando apologised for theearliness of his visit. It seemed to me as he entered the room andtook the chair that was offered to him, that he was the greater manof the two on the occasion,--or perhaps I should say of the three.And yet he had not before come on shore to visit me, nor had hemade one at our little dinner-party. "Mr Neverbend," began thecaptain,--and I observed that up to that moment he had generallyaddressed me as President,--"it cannot be denied that we have comehere on an unpleasant mission. You have received us with all thatcourtesy and hospitality for which your character in England standsso high. But you must be aware that it has been our intention tointerfere with that which you must regard as the performance of aduty."

"It is a duty," said I. "But your power is so superior to any thatI can advance, as to make us here feel that there is no disgrace inyielding to it. Therefore we can be courteous while we submit. Not adoubt but had your force been only double or treble our own, I shouldhave found it my duty to struggle with you. But how can a littleState, but a few years old, situated on a small island, far removedfrom all the centres of civilisation, contend on any point with theowner of the great 250-ton swiveller-gun?"

"That is all quite true, Mr Neverbend," said Sir Ferdinando Brown.

"I can afford to smile, because I am absolutely powerless before you;but I do not the less feel that, in a matter in which the progress ofthe world is concerned, I, or rather we, have been put down by bruteforce. You have come to us threatening us with absolute destruction.Whether your gun be loaded or not matters little."

"It is certainly loaded," said Captain Battleax.

"Then you have wasted your powder and shot. Like a highwayman, itwould have sufficed for you merely to tell the weak and cowardly thatyour pistol would be made to go off when wanted. To speak the truth,Captain Battleax, I do not think that you excel us more in couragethan you do in thought and practical wisdom. Therefore, I feel myselfquite able, as President of this republic, to receive you with acourtesy due to the servants of a friendly ally."

"Very well put," said Sir Ferdinando. I simply bowed to him. "Andnow," he continued, "will you answer me one question?"

"A dozen if it suits you to ask them."

"Captain Battleax cannot remain here long with that expensive toywhich he keeps locked up somewhere among his cocked-hats and whitegloves. I can assure you he has not even allowed me to see thetrigger since I have been on board. But 250-ton swivellers do costmoney, and the John Bright must steam away, and play its part inother quarters of the globe. What do you intend to do when he shallhave taken his pocket-pistol away?"

I thought for a little what answer it would best become me to giveto this question, but I paused only for a moment or two. "I shallproceed at once to carry out the Fixed Period." I felt that my honourdemanded that to such a question I should make no other reply.

"And that in opposition to the wishes, as I understand, of a largeproportion of your fellow-citizens?"

"The wishes of our fellow-citizens have been declared by repeatedmajorities in the Assembly."

"You have only one House in your Constitution," said Sir Ferdinando.

"One House I hold to be quite sufficient."

I was proceeding to explain the theory on which the BritannulanConstitution had been formed, when Sir Ferdinando interrupted me. "Atany rate, you will admit that a second Chamber is not there to guardagainst the sudden action of the first. But we need not discuss allthis now. It is your purpose to carry out your Fixed Period as soonas the John Bright shall have departed?"

"Certainly."

"And you are, I am aware, sufficiently popular with the people hereto enable you to do so?"

"I think I am," I said, with a modest acquiescence in an assertionwhich I felt to be so m

uch to my credit. But I blushed for itsuntruth.

"Then," said Sir Ferdinando, "there is nothing for it but that hemust take you with him."

There came upon me a sudden shock when I heard these words, whichexceeded anything which I had yet felt. Me, the President of aforeign nation, the first officer of a people with whom Great Britainwas at peace,--the captain of one of her gunboats must carry me off,hurry me away a prisoner, whither I knew not, and leave the countryungoverned, with no President as yet elected to supply my place! AndI, looking at the matter from my own point of view, was a husband,the head of a family, a man largely concerned in business,--I was tobe carried away in bondage--I, who had done no wrong, had disobeyedno law, who had indeed been conspicuous for my adherence to myduties! No opposition ever shown to Columbus and Galileo had comenear to this in audacity and oppression. I, the President of a freerepublic, the elected of all its people, the chosen depository of itsofficial life,--I was to be kidnapped and carried off in a ship ofwar, because, forsooth, I was deemed too popular to rule the country!And this was told to me in my own room in the executive chambers, inthe very sanctum of public life, by a stout florid gentleman in ablack coat, of whom I hitherto knew nothing except that his name wasBrown!

"Sir," I said, after a pause, and turning to Captain Battleax andaddressing him, "I cannot believe that you, as an officer in theBritish navy, will commit any act of tyranny so oppressive, and ofinjustice so gross, as that which this gentleman has named."

"You hear what Sir Ferdinando Brown has said," replied CaptainBattleax.

"I do not know the gentleman,--except as having been introduced tohim at your hospitable table. Sir Ferdinando Brown is to me--simplySir Ferdinando Brown."

"Sir Ferdinando has lately been our British Governor in Ashantee,where he has, as I may truly say, 'bought golden opinions from allsorts of people.' He has now been sent here on this delicate mission,and to no one could it be intrusted by whom it would be performedwith more scrupulous honour." This was simply the opinion of CaptainBattleax, and expressed in the presence of the gentleman himself whomhe so lauded.

"But what is the delicate mission?" I asked.

Then Sir Ferdinando told his whole story, which I think should havebeen declared before I had been asked to sit down to dinner with himin company with the captain on board the ship. I was to be taken awayand carried to England or elsewhere,--or drowned upon the voyage,it mattered not which. That was the first step to be taken towardscarrying out the tyrannical, illegal, and altogether injuriousintention of the British Government. Then the republic of Britannulawas to be declared as non-existent, and the British flag was to beexalted, and a British Governor installed in the executive chambers!That Governor was to be Sir Ferdinando Brown.

I was lost in a maze of wonderment as I attempted to look at theproceeding all round. Now, at the close of the twentieth century,could oppression be carried to such a height as this? "Gentlemen," Isaid, "you are powerful. That little instrument which you have hiddenin your cabin makes you the master of us all. It has been preparedby the ingenuity of men, able to dominate matter though altogetherpowerless over mind. On myself, I need hardly say that it would beinoperative. Though you should reduce me to atoms, from them wouldspring those opinions which would serve altogether to silence yourartillery. But the dread of it is to the generality much morepowerful than the fact of its possession."

"You may be quite sure it's there," said Captain Battleax, "and thatI can so use it as to half obliterate your town within two minutes ofmy return on board."

"You propose to kidnap me," I said. "What would become of your gunwere I to kidnap you?"

"Lieutenant Crosstrees has sealed orders, and is practicallyacquainted with the mechanism of the gun. Lieutenant Crosstrees isa very gallant officer. One of us always remains on board while theother is on shore. He would think nothing of blowing me up, so longas he obeyed orders."

"I was going on to observe," I continued, "that though this poweris in your hands, and in that of your country, the exercise of itbetrays not only tyranny of disposition, but poorness and meannessof spirit." I here bowed first to the one gentleman, and then to theother. "It is simply a contest between brute strength and mentalenergy."

"If you will look at the contests throughout the world," said SirFerdinando, "you will generally find that the highest respect is paidto the greatest battalions."

"What world-wide iniquity such a speech as that discloses!" said I,still turning myself to the captain; for though I would have crushedthem both by my words had it been possible, my dislike centred itselfon Sir Ferdinando. He was a man who looked as though everything wereto yield to his meagre philosophy; and it seemed to me as though heenjoyed the exercise of the tyranny which chance had put into hispower.

"You will allow me to suggest," said he, "that that is a matter ofopinion. In the meantime, my friend Captain Battleax has below aguard of fifty marines, who will pay you the respect of escorting youon board with two of the ship's cutters. Everything that can be theredone for your accommodation and comfort,--every luxury which can beprovided to solace the President of this late republic,--shall beafforded. But, Mr Neverbend, it is necessary that you should go toEngland; and allow me to assure you, that your departure can neitherbe prevented nor delayed by uncivil words spoken to the futureGovernor of this prosperous colony."

"My words are, at any rate, less uncivil than Captain Battleax'smarines; and they have, I submit, been made necessary by the conductof your country in this matter. Were I to comply with your orderswithout expressing my own opinion, I should seem to have done sowillingly hereafter. I say that the English Government is a tyrant,and that you are the instruments of its tyranny. Now you can proceedto do your work."

"That having all been pleasantly settled," said Sir Ferdinando, witha smile, "I will ask you to read the document by which this duty hasbeen placed in my hands." He then took out of his pocket a letteraddressed to him by the Duke of Hatfield, as Minister for the CrownColonies, and gave it to me to read. The letter ran as follows:--

COLONIAL OFFICE, CROWN COLONIES, 15th May 1980.

SIR,--I have it in command to inform your Excellency that you have been appointed Governor of the Crown colony which is called Britannula. The peculiar circumstances of the colony are within your Excellency's knowledge. Some years since, after the separation of New Zealand, the inhabitants of Britannula requested to be allowed to manage their own affairs, and H.M. Minister of the day thought it expedient to grant their request. The country has since undoubtedly prospered, and in a material point of view has given us no grounds for regret. But in their selection of a Constitution the Britannulists have unfortunately allowed themselves but one deliberative assembly, and hence have sprung their present difficulties. It must be, that in such circumstances crude councils should be passed as laws without the safeguard coming from further discussion and thought. At the present moment a law has been passed which, if carried into action, would become abhorrent to mankind at large. It is contemplated to destroy all those who shall have reached a certain fixed age. The arguments put forward to justify so strange a measure I need not here explain at length. It is founded on the acknowledged weakness of those who survive that period of life at which men cease to work. This terrible doctrine has been adopted at the advice of an eloquent citizen of the republic, who is at present its President, and whose general popularity seems to be so great, that, in compliance with his views, even this measure will be carried out unless Great Britain shall interfere.

You are desired to proceed at once to Britannula, to reannex the island, and to assume the duties of the Governor of a Crown colony. It is understood that a year of probation is to be allowed to those victims who have agreed to their own immolation. You will therefore arrive there in ample time to prevent the first bloodshed. But it is surmised that you will find difficulties in the way of your entering at once upon your government. So great is the

popularity of their President, Mr Neverbend, that, if he be left on the island, your Excellency will find a dangerous rival. It is therefore desired that you should endeavour to obtain information as to his intentions; and that, if the Fixed Period be not abandoned altogether, with a clear conviction as to its cruelty on the part of the inhabitants generally, you should cause him to be carried away and brought to England.

To enable you to effect this, Captain Battleax, of H.M. gunboat the John Bright, has been instructed to carry you out. The John Bright is armed with a weapon of great power, against which it is impossible that the people of Britannula should prevail. You will carry out with you 100 men of the North-north-west Birmingham regiment, which will probably suffice for your own security, as it is thought that if Mr Neverbend be withdrawn, the people will revert easily to their old habits of obedience.

In regard to Mr Neverbend himself, it is the especial wish of H.M. Government that he shall be treated with all respect, and that those honours shall be paid to him which are due to the President of a friendly republic. It is to be expected that he should not allow himself to make an enforced visit to England without some opposition; but it is considered in the interests of humanity to be so essential that this scheme of the Fixed Period shall not be carried out, that H.M. Government consider that his absence from Britannula shall be for a time insured. You will therefore insure it; but will take care that, as far as lies in your Excellency's power, he be treated with all that respect and hospitality which would be due to him were he still the President of an allied republic.

Captain Battleax, of the John Bright, will have received a letter to the same effect from the First Lord of the Admiralty, and you will find him ready to co-operate with your Excellency in every respect.--I have the honour to be, sir, your Excellency's most obedient servant,

HATFIELD.

This I read with great attention, while they sat silent. "Iunderstand it; and that is all, I suppose, that I need say upon thesubject. When do you intend that the John Bright shall start?"

"We have already lighted our fires, and our sailors are weighing theanchors. Will twelve o'clock suit you?"

"To-day!" I shouted.

"I rather think we must move to-day," said the captain.

"If so, you must be content to take my dead body. It is now nearlyeleven."

"Half-past ten," said the captain, looking at his watch.

"And I have no one ready to whom I can give up the archives of theGovernment."

"I shall be happy to take charge of them," said Sir Ferdinando.

"No doubt,--knowing nothing of the forms of our government, or--"

"They, of course, must all be altered."

"Or of the habits of our people. It is quite impossible. I, too, havethe complicated affairs of my entire life to arrange, and my wife andson to leave though I would not for a moment be supposed to put theseprivate matters forward when the public service is concerned. But thetime you name is so unreasonable as to create a feeling of horror atyour tyranny."

"A feeling of horror would be created on the other side of thewater," said Sir Ferdinando, "at the idea of what you may do ifyou escape us. I should not consider my head to be safe on my ownshoulders were it to come to pass that while I am on the island anold man were executed in compliance with your system."

Alas! I could not but feel how little he knew of the sentiment whichprevailed in Britannula; how false was his idea of my power; and howpotent was that love of life which had been evinced in the city whenthe hour for deposition had become nigh. All this I could hardlyexplain to him, as I should thus be giving to him the strongestevidence against my own philosophy. And yet it was necessary thatI should say something to make him understand that this suddendeportation was not necessary. And then during that moment there cameto me suddenly an idea that it might be well that I should take thisjourney to England, and there begin again my career,--as Columbus,after various obstructions, had recommenced his,--and that I shouldendeavour to carry with me the people of Great Britain, as Ihad already carried the more quickly intelligent inhabitants ofBritannula. And in order that I may do so, I have now prepared thesepages, writing them on board H.M. gunboat, the John Bright.

"Your power is sufficient," I said.

"We are not sure of that," said Sir Ferdinando. "It is always well tobe on the safe side."

"Are you so afraid of what a single old man can do,--you withyour 250-ton swivellers, and your guard of marines, and yourNorth-north-west Birmingham soldiery?"

"That depends on who and what the old man may be." This was thefirst complimentary speech which Sir Ferdinando had made, and Imust confess that it was efficacious. I did not after that feel sostrong a dislike to the man as I had done before. "We do not wishto make ourselves disagreeable to you, Mr Neverbend." I shrugged myshoulders. "Unnecessarily disagreeable, I should have said. You area man of your word." Here I bowed to him. "If you will give us yourpromise to meet Captain Battleax here at this time to-morrow, wewill stretch a point and delay the departure of the John Bright fortwenty-four hours." To this again I objected violently; and at last,as an extreme favour, two entire days were allowed for my departure.

The craft of men versed in the affairs of the old Eastern worldis notorious. I afterwards learned that the stokers on board theship were only pretending to get up their fires, and the sailorspretending to weigh their anchors, in order that their operationsmight be visible, and that I might suppose that I had received agreat favour from my enemies' hands. And this plan was adopted, too,in order to extract from me a promise that I would depart in peace.At any rate, I did make the promise, and gave these two gentlemen myword that I would be present there in my own room in the executivechambers at the same hour on the day but one following.

"And now," said Sir Ferdinando, "that this matter is settled betweenus, allow me most cordially to shake you by the hand, and to expressmy great admiration for your character. I cannot say that I agreewith you in theory as to the Fixed Period,--my wife and childrencould not, I am sure, endure to see me led away when a certain dayshould come,--but I can understand that much may be said on thepoint, and I admire greatly the eloquence and energy which you havedevoted to the matter. I shall be happy to meet you here at any hourto-morrow, and to receive the Britannulan archives from your hands.You, Mr Neverbend, will always be regarded as the father of yourcountry--

'Roma patrem patriae Ciceronem libera dixit.'"

With this the two gentlemen left the room.

Doctor Thorne

Doctor Thorne Can You Forgive Her?

Can You Forgive Her? The Last Chronicle of Barset

The Last Chronicle of Barset The Fixed Period

The Fixed Period Phineas Redux

Phineas Redux The Way We Live Now

The Way We Live Now Castle Richmond

Castle Richmond The Bertrams

The Bertrams An Old Man's Love

An Old Man's Love The Belton Estate

The Belton Estate Marion Fay: A Novel

Marion Fay: A Novel The Claverings

The Claverings The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson

The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson Nina Balatka

Nina Balatka The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp

The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp Barchester Towers cob-2

Barchester Towers cob-2 The Chronicles of Barsetshire

The Chronicles of Barsetshire The Warden cob-1

The Warden cob-1 Framley Parsonage

Framley Parsonage Christmas at Thompson Hall

Christmas at Thompson Hall The Warden

The Warden The Palliser Novels

The Palliser Novels The Small House at Allington

The Small House at Allington Barchester Towers

Barchester Towers The Small House at Allington cob-5

The Small House at Allington cob-5 The Duke's Children

The Duke's Children Phineas Finn, the Irish Member

Phineas Finn, the Irish Member Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope