- Home

- Anthony Trollope

The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp

The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp Read online

Transcribed from the 1864 Chapman and Hall “Tales of All Countries”edition by David Price, email [email protected]

THE RELICS OF GENERAL CHASSÉ A TALE OF ANTWERP.

THAT Belgium is now one of the European kingdoms, living by its own laws,resting on its own bottom, with a king and court, palaces and parliamentof its own, is known to all the world. And a very nice little kingdom itis; full of old towns, fine Flemish pictures, and interesting Gothicchurches. But in the memory of very many of us who do not thinkourselves old men, Belgium, as it is now called—in those days it used tobe Flanders and Brabant—was a part of Holland; and it obtained its ownindependence by a revolution. In that revolution the most importantmilitary step was the siege of Antwerp, which was defended on the part ofthe Dutch by General Chassé, with the utmost gallantry, but neverthelessineffectually.

After the siege Antwerp became quite a show place; and among the visitorswho flocked there to talk of the gallant general, and to see whatremained of the great effort which he had made to defend the place, weretwo Englishmen. One was the hero of this little history; and the otherwas a young man of considerably less weight in the world. The less I sayof the latter the better; but it is necessary that I should give somedescription of the former.

The Rev. Augustus Horne was, at the time of my narrative, a beneficedclergyman of the Church of England. The profession which he had gracedsat easily on him. Its external marks and signs were as pleasing to hisfriends as were its internal comforts to himself. He was a man of muchquiet mirth, full of polished wit, and on some rare occasions he coulddescend to the more noisy hilarity of a joke. Loved by his friends heloved all the world. He had known no care and seen no sorrow. Alwaysintended for holy orders he had entered them without a scruple, andremained within their pale without a regret. At twenty-four he had beena deacon, at twenty-seven a priest, at thirty a rector, and atthirty-five a prebendary; and as his rectory was rich and his prebendalstall well paid, the Rev. Augustus Horne was called by all, and calledhimself, a happy man. His stature was about six feet two, and hiscorpulence exceeded even those bounds which symmetry would have preferredas being most perfectly compatible even with such a height. Butnevertheless Mr. Horne was a well-made man; his hands and feet weresmall; his face was handsome, frank, and full of expression; his brighteyes twinkled with humour; his finely-cut mouth disclosed two marvellousrows of well-preserved ivory; and his slightly aquiline nose was justsuch a projection as one would wish to see on the face of a well-fedgood-natured dignitary of the Church of England. When I add to all thisthat the reverend gentleman was as generous as he was rich—and the kindmother in whose arms he had been nurtured had taken care that he shouldnever want—I need hardly say that I was blessed with a very pleasanttravelling companion.

I must mention one more interesting particular. Mr. Horne was ratherinclined to dandyism, in an innocent way. His clerical starchedneckcloth was always of the whitest, his cambric handkerchief of thefinest, his bands adorned with the broadest border; his sable suit neverdegenerated to a rusty brown; it not only gave on all occasions glossyevidence of freshness, but also of the talent which the artisan haddisplayed in turning out a well-dressed clergyman of the Church ofEngland. His hair was ever brushed with scrupulous attention, and showedin its regular waves the guardian care of each separate bristle. And allthis was done with that ease and grace which should be thecharacteristics of a dignitary of the established English Church.

I had accompanied Mr. Horne to the Rhine; and we had reached Brussels onour return, just at the close of that revolution which ended in affordinga throne to the son-in-law of George the Fourth. At that moment GeneralChassé’s name and fame were in every man’s mouth, and, like other curiousadmirers of the brave, Mr. Horne determined to devote two days to thescene of the late events at Antwerp. Antwerp, moreover, possessesperhaps the finest spire, and certainly one of the three or four finestpictures, in the world. Of General Chassé, of the cathedral, and of theRubens, I had heard much, and was therefore well pleased that such shouldbe his resolution. This accomplished we were to return to Brussels; andthence, via Ghent, Ostend, and Dover, I to complete my legal studies inLondon, and Mr. Horne to enjoy once more the peaceful retirement ofOllerton rectory. As we were to be absent from Brussels but one night wewere enabled to indulge in the gratification of travelling without ourluggage. A small sac-de-nuit was prepared; brushes, combs, razors,strops, a change of linen, &c. &c., were carefully put up; but our heavybaggage, our coats, waistcoats, and other wearing apparel wereunnecessary. It was delightful to feel oneself so light-handed. Thereverend gentleman, with my humble self by his side, left the portal ofthe Hôtel de Belle Vue at 7 a.m., in good humour with all the world.There were no railroads in those days; but a cabriolet, big enough tohold six persons, with rope traces and corresponding appendages,deposited us at the Golden Fleece in something less than six hours. Theinward man was duly fortified, and we started for the castle.

It boots not here to describe the effects which gunpowder and grape-shothad had on the walls of Antwerp. Let the curious in these matters readthe horrors of the siege of Troy, or the history of Jerusalem taken byTitus. The one may be found in Homer, and the other in Josephus. Or ifthey prefer doings of a later date there is the taking of Sebastopol, asnarrated in the columns of the “Times” newspaper. The accounts areequally true, instructive, and intelligible. In the mean time allow theRev. Augustus Horne and myself to enter the private chambers of therenowned though defeated general.

We rambled for a while through the covered way, over the glacis and alongthe counterscarp, and listened to the guide as he detailed to us, inalready accustomed words, how the siege had gone. Then we got into theprivate apartments of the general, and, having dexterously shaken off ourattendant, wandered at large among the deserted rooms.

“It is clear that no one ever comes here,” said I.

“No,” said the Rev. Augustus; “it seems not; and to tell the truth, Idon’t know why any one should come. The chambers in themselves are notattractive.”

What he said was true. They were plain, ugly, square, unfurnished rooms,here a big one, and there a little one, as is usual in mosthouses;—unfurnished, that is, for the most part. In one place we didfind a table and a few chairs, in another a bedstead, and so on. But tome it was pleasant to indulge in those ruminations which any traces ofthe great or unfortunate create in softly sympathising minds. For a timewe communicated our thoughts to each other as we roamed free as airthrough the apartments; and then I lingered for a few moments behind,while Mr. Horne moved on with a quicker step.

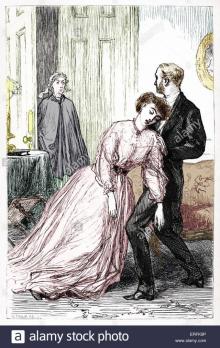

At last I entered the bedchamber of the general, and there I overtook myfriend. He was inspecting, with much attention, an article of the greatman’s wardrobe which he held in his hand. It was precisely that virilehabiliment to which a well-known gallant captain alludes in hisconversation with the posthumous appearance of Miss Bailey, as containinga Bank of England £5 note.

“The general must have been a large man, George, or he would hardly havefilled these,” said Mr. Horne, holding up to the light the respectableleathern articles in question. “He must have been a very large man,—thelargest man in Antwerp, I should think; or else his tailor has done himmore than justice.”

They were certainly large, and had about them a charming regimentalmilitary appearance. They were made of white leather, with bright metalbuttons at the knees and bright metal buttons at the top. They owned nopockets, and were, with the exception of the legitimate outlet,continuous in the circumference of the waistband. No dangling stringsgave them an appea

rance of senile imbecility. Were it not for a certainrigidity, sternness, and mental inflexibility,—we will call it militaryardour,—with which they were imbued, they would have created envy in thebosom of a fox-hunter.

Mr. Horne was no fox-hunter, but still he seemed to be irresistibly takenwith the lady-like propensity of wishing to wear them. “Surely, George,”he said, “the general must have been a stouter man than I am”—and hecontemplated his own proportions with complacency—“these what’s-the-namesare quite big enough for me.”

I differed in opinion, and was obliged to explain that I thought he didthe good living of Ollerton insufficient justice.

“I am sure they are large enough for me,” he repeated, with considerableobstinacy. I smiled incredulously; and then to settle the matter heresolved that he would try them on. Nobody had been in these rooms forthe last hour, and it appeared as though they were never visited. Eventhe guide had not come on with us, but was employed in showing otherparties about the fortifications. It was clear

Doctor Thorne

Doctor Thorne Can You Forgive Her?

Can You Forgive Her? The Last Chronicle of Barset

The Last Chronicle of Barset The Fixed Period

The Fixed Period Phineas Redux

Phineas Redux The Way We Live Now

The Way We Live Now Castle Richmond

Castle Richmond The Bertrams

The Bertrams An Old Man's Love

An Old Man's Love The Belton Estate

The Belton Estate Marion Fay: A Novel

Marion Fay: A Novel The Claverings

The Claverings The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson

The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson Nina Balatka

Nina Balatka The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp

The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp Barchester Towers cob-2

Barchester Towers cob-2 The Chronicles of Barsetshire

The Chronicles of Barsetshire The Warden cob-1

The Warden cob-1 Framley Parsonage

Framley Parsonage Christmas at Thompson Hall

Christmas at Thompson Hall The Warden

The Warden The Palliser Novels

The Palliser Novels The Small House at Allington

The Small House at Allington Barchester Towers

Barchester Towers The Small House at Allington cob-5

The Small House at Allington cob-5 The Duke's Children

The Duke's Children Phineas Finn, the Irish Member

Phineas Finn, the Irish Member Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope