- Home

- Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope Read online

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope

Энтони Троллоп

EBook of Autobiography of Anthony Trollope by Anthony Trollope (www.anthonytrollope.com)

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Preface

It may be well that I should put a short preface to this book. In

the summer of 1878 my father told me that he had written a memoir

of his own life. He did not speak about it at length, but said

that he had written me a letter, not to be opened until after his

death, containing instructions for publication.

This letter was dated 30th April, 1876. I will give here as much

of it as concerns the public: "I wish you to accept as a gift from

me, given you now, the accompanying pages which contain a memoir

of my life. My intention is that they shall be published after

my death, and be edited by you. But I leave it altogether to your

discretion whether to publish or to suppress the work;--and also

to your discretion whether any part or what part shall be omitted.

But I would not wish that anything should be added to the memoir.

If you wish to say any word as from yourself, let it be done in

the shape of a preface or introductory chapter." At the end there

is a postscript: "The publication, if made at all, should be effected

as soon as possible after my death." My father died on the 6th of

December, 1882.

It will be seen, therefore, that my duty has been merely to pass

the book through the press conformably to the above instructions.

I have placed headings to the right-hand pages throughout the book,

and I do not conceive that I was precluded from so doing. Additions

of any other sort there have been none; the few footnotes are my

father's own additions or corrections. And I have made no alterations.

I have suppressed some few passages, but not more than would amount

to two printed pages has been omitted. My father has not given any

of his own letters, nor was it his wish that any should be published.

So much I would say by way of preface. And I think I may also give

in a few words the main incidents in my father's life after he

completed his autobiography.

He has said that he had given up hunting; but he still kept two

horses for such riding as may be had in or about the immediate

neighborhood of London. He continued to ride to the end of his

life: he liked the exercise, and I think it would have distressed

him not to have had a horse in his stable. But he never spoke

willingly on hunting matters. He had at last resolved to give up

his favourite amusement, and that as far as he was concerned there

should be an end of it. In the spring of 1877 he went to South

Africa, and returned early in the following year with a book on

the colony already written. In the summer of 1878, he was one of

a party of ladies and gentlemen who made an expedition to Iceland

in the "Mastiff," one of Mr. John Burns' steam-ships. The journey

lasted altogether sixteen days, and during that time Mr. and Mrs.

Burns were the hospitable entertainers. When my father returned,

he wrote a short account of How the "Mastiffs" went to Iceland.

The book was printed, but was intended only for private circulation.

Every day, until his last illness, my father continued his work.

He would not otherwise have been happy. He demanded from himself

less than he had done ten years previously, but his daily task was

always done. I will mention now the titles of his books that were

published after the last included in the list which he himself has

given at the end of the second volume:--

An Eye for an Eye, . . . . 1879

Cousin Henry, . . . . . . 1879

Thackeray, . . . . . . . 1879

The Duke's Children, . . . . 1880

Life of Cicero, . . . . . 1880

Ayala's Angel, . . . . . 1881

Doctor Wortle's School, . . . 1881

Frau Frohmann and other Stories, . 1882

Lord Palmerston, . . . . . 1882

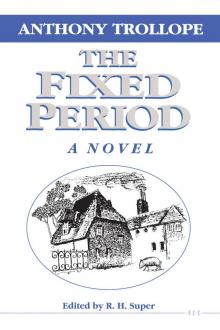

The Fixed Period, . . . . . 1882

Kept in the Dark, . . . . . 1882

Marion Fay, . . . . . . 1882

Mr. Scarborough's Family, . . . 1883

At the time of his death he had written four-fifths of an Irish

story, called The Landleaguers, shortly about to be published; and

he left in manuscript a completed novel, called An Old Man's Love,

which will be published by Messrs. Blackwood & Sons in 1884.

In the summer of 1880 my father left London, and went to live at

Harting, a village in Sussex, but on the confines of Hampshire. I

think he chose that spot because he found there a house that suited

him, and because of the prettiness of the neighborhood. His last

long journey was a trip to Italy in the late winter and spring of

1881; but he went to Ireland twice in 1882. He went there in May

of that year, and was then absent nearly a month. This journey did

him much good, for he found that the softer atmosphere relieved

his asthma, from which he had been suffering for nearly eighteen

months. In August following he made another trip to Ireland, but

from this journey he derived less benefit. He was much interested

in, and was very much distressed by, the unhappy condition of the

country. Few men know Ireland better than he did. He had lived

there for sixteen years, and his Post Office word had taken him

into every part of the island. In the summer of 1882 he began his

last novel, The Landleaguers, which, as stated above, was unfinished

when he died. This book was a cause of anxiety to him. He could not

rid his mind of the fact that he had a story already in the course

of publication, but which he had not yet completed. In no other

case, except Framley Parsonage, did my father publish even the

first number of any novel before he had fully completed the whole

tale.

On the evening of the 3rd of November, 1882, he was seized with

paralysis on the right side, accompanied by loss of speech. His

mind had also failed, though at intervals his thoughts would return

to him. After the first three weeks these lucid intervals became

rarer, but it was always very difficult to tell how far his mind

was sound or how far astray. He died on the evening of the 6th of

December following, nearly five weeks from the night of his attack.

I have been led to say these few words, not at all from a desire

to supplement my father's biography of himself, but to mention the

main incidents in his life after he had finished his own record. In

what I have here said I do not think I have exceeded his instructions.

Henry M. Trollope.

September, 1883.

CHAPTER I My education 1815-1834

In writing these pages, which, for the want of a better name, I shall

be fain to call the autobiograp

hy of so insignificant a person as

myself, it will not be so much my intention to speak of the little

details of my private life, as of what I, and perhaps others round

me, have done in literature; of my failures and successes such as

they have been, and their causes; and of the opening which a literary

career offers to men and women for the earning of their bread. And

yet the garrulity of old age, and the aptitude of a man's mind to

recur to the passages of his own life, will, I know, tempt me to say

something of myself;--nor, without doing so, should I know how to

throw my matter into any recognised and intelligible form. That I,

or any man, should tell everything of himself, I hold to be impossible.

Who could endure to own the doing of a mean thing? Who is there

that has done none? But this I protest:--that nothing that I say

shall be untrue. I will set down naught in malice; nor will I give

to myself, or others, honour which I do not believe to have been

fairly won. My boyhood was, I think, as unhappy as that of a young

gentleman could well be, my misfortunes arising from a mixture of

poverty and gentle standing on the part of my father, and from an

utter want on my part of the juvenile manhood which enables some

boys to hold up their heads even among the distresses which such

a position is sure to produce.

I was born in 1815, in Keppel Street, Russell Square; and while a

baby, was carried down to Harrow, where my father had built a house

on a large farm which, in an evil hour he took on a long lease from

Lord Northwick. That farm was the grave of all my father's hopes,

ambition, and prosperity, the cause of my mother's sufferings, and

of those of her children, and perhaps the director of her destiny

and of ours. My father had been a Wykamist and a fellow of New

College, and Winchester was the destination of my brothers and

myself; but as he had friends among the masters at Harrow, and as

the school offered an education almost gratuitous to children living

in the parish, he, with a certain aptitude to do things differently

from others, which accompanied him throughout his life, determined

to use that august seminary as "t'other school" for Winchester, and

sent three of us there, one after the other, at the age of seven.

My father at this time was a Chancery barrister practising in

London, occupying dingy, almost suicidal chambers, at No. 23 Old

Square, Lincoln's Inn,--chambers which on one melancholy occasion

did become absolutely suicidal. [Footnote: A pupil of his destroyed

himself in the rooms.] He was, as I have been informed by those

quite competent to know, an excellent and most conscientious lawyer,

but plagued with so bad a temper, that he drove the attorneys from

him. In his early days he was a man of some small fortune and of

higher hopes. These stood so high at the time of my birth, that

he was felt to be entitled to a country house, as well as to that

in Keppel Street; and in order that he might build such a residence,

he took the farm. This place he called Julians, and the land runs

up to the foot of the hill on which the school and the church

stand,--on the side towards London. Things there went much against

him; the farm was ruinous, and I remember that we all regarded the

Lord Northwick of those days as a cormorant who was eating us up.

My father's clients deserted him. He purchased various dark gloomy

chambers in and about Chancery Lane, and his purchases always went

wrong. Then, as a final crushing blow, and old uncle, whose heir he

was to have been, married and had a family! The house in London was

let; and also the house he built at Harrow, from which he descended

to a farmhouse on the land, which I have endeavoured to make known

to some readers under the name of Orley Farm. This place, just as it

was when we lived there, is to be seen in the frontispiece to the

first edition of that novel, having the good fortune to be delineated

by no less a pencil than that of John Millais.

My two elder brothers had been sent as day-boarders to Harrow

School from the bigger house, and may probably have been received

among the aristocratic crowd,--not on equal terms, because a

day-boarder at Harrow in those days was never so received,--but at

any rate as other day-boarders. I do not suppose that they were well

treated, but I doubt whether they were subjected to the ignominy

which I endured. I was only seven, and I think that boys at seven

are now spared among their more considerate seniors. I was never

spared; and was not even allowed to run to and fro between our house

and the school without a daily purgatory. No doubt my appearance

was against me. I remember well, when I was still the junior boy

in the school, Dr. Butler, the head-master, stopping me in the

street, and asking me, with all the clouds of Jove upon his brow

and the thunder in his voice, whether it was possible that Harrow

School was disgraced by so disreputably dirty a boy as I! Oh, what

I felt at that moment! But I could not look my feelings. I do not

doubt that I was dirty;--but I think that he was cruel. He must

have known me had he seen me as he was wont to see me, for he was

in the habit of flogging me constantly. Perhaps he did not recognise

me by my face.

At this time I was three years at Harrow; and, as far as I can

remember, I was the junior boy in the school when I left it.

Then I was sent to a private school at Sunbury, kept by Arthur

Drury. This, I think, must have been done in accordance with the

advice of Henry Drury, who was my tutor at Harrow School, and my

father's friend, and who may probably have expressed an opinion that

my juvenile career was not proceeding in a satisfactory manner at

Harrow. To Sunbury I went, and during the two years I was there,

though I never had any pocket-money, and seldom had much in the

way of clothes, I lived more nearly on terms of equality with other

boys than at any other period during my very prolonged school-days.

Even here, I was always in disgrace. I remember well how, on one

occasion, four boys were selected as having been the perpetrators

of some nameless horror. What it was, to this day I cannot even

guess; but I was one of the four, innocent as a babe, but adjudged

to have been the guiltiest of the guilty. We each had to write out

a sermon, and my sermon was the longest of the four. During the

whole of one term-time we were helped last at every meal. We were

not allowed to visit the playground till the sermon was finished.

Mine was only done a day or two before the holidays. Mrs. Drury,

when she saw us, shook her head with pitying horror. There were

ever so many other punishments accumulated on our heads. It broke

my heart, knowing myself to be innocent, and suffering also under

the almost equally painful feeling that the other three--no doubt

wicked boys--were the curled darlings of the school, who would never

have selected me to share their wickedness with them. I contrived

to learn, from words that fe

ll from Mr. Drury, that he condemned

me because I, having come from a public school, might be supposed

to be the leader of wickedness! On the first day of the next term

he whispered to me half a word that perhaps he had been wrong.

With all a stupid boy's slowness, I said nothing; and he had not

the courage to carry reparation further. All that was fifty years

ago, and it burns me now as though it were yesterday. What lily-livered

curs those boys must have been not to have told the truth!--at any

rate as far as I was concerned. I remember their names well, and

almost wish to write them here.

When I was twelve there came the vacancy at Winchester College which

I was destined to fill. My two elder brothers had gone there, and

the younger had been taken away, being already supposed to have lost

his chance of New College. It had been one of the great ambitions

of my father's life that his three sons, who lived to go to Winchester,

should all become fellows of New College. But that suffering man

was never destined to have an ambition gratified. We all lost the

prize which he struggled with infinite labour to put within our

reach. My eldest brother all but achieved it, and afterwards went

to Oxford, taking three exhibitions from the school, though he

lost the great glory of a Wykamist. He has since made himself well

known to the public as a writer in connection with all Italian

subjects. He is still living as I now write. But my other brother

died early.

While I was at Winchester my father's affairs went from bad to worse.

He gave up his practice at the bar, and, unfortunate that he was,

took another farm. It is odd that a man should conceive,--and in

this case a highly educated and a very clever man,--that farming

should be a business in which he might make money without any

special education or apprenticeship. Perhaps of all trades it is

the one in which an accurate knowledge of what things should be

done, and the best manner of doing them, is most necessary. And it is

one also for success in which a sufficient capital is indispensable.

He had no knowledge, and, when he took this second farm, no capital.

This was the last step preparatory to his final ruin.

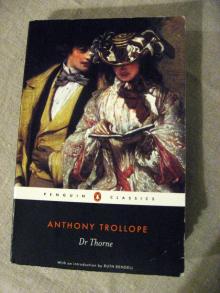

Doctor Thorne

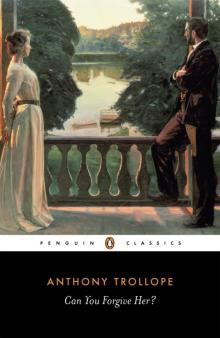

Doctor Thorne Can You Forgive Her?

Can You Forgive Her? The Last Chronicle of Barset

The Last Chronicle of Barset The Fixed Period

The Fixed Period Phineas Redux

Phineas Redux The Way We Live Now

The Way We Live Now Castle Richmond

Castle Richmond The Bertrams

The Bertrams An Old Man's Love

An Old Man's Love The Belton Estate

The Belton Estate Marion Fay: A Novel

Marion Fay: A Novel The Claverings

The Claverings The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson

The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson Nina Balatka

Nina Balatka The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp

The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp Barchester Towers cob-2

Barchester Towers cob-2 The Chronicles of Barsetshire

The Chronicles of Barsetshire The Warden cob-1

The Warden cob-1 Framley Parsonage

Framley Parsonage Christmas at Thompson Hall

Christmas at Thompson Hall The Warden

The Warden The Palliser Novels

The Palliser Novels The Small House at Allington

The Small House at Allington Barchester Towers

Barchester Towers The Small House at Allington cob-5

The Small House at Allington cob-5 The Duke's Children

The Duke's Children Phineas Finn, the Irish Member

Phineas Finn, the Irish Member Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope