- Home

- Anthony Trollope

The Small House at Allington

The Small House at Allington Read online

THE SMALL HOUSE AT ALLINGTON

ANTHONY TROLLOPE was born in London in 1815 and died in 1882. His father was a barrister who went bankrupt and the family was maintained by his mother, Frances, who resourcefully in later life became a bestselling writer. His education was disjointed and his childhood generally seems to have been an unhappy one.

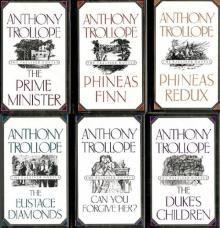

Trollope enjoyed considerable acclaim as a novelist during his life-time, publishing over forty novels and many short stories, at the same time following a notable career as a senior civil servant in the Post Office. The Warden (1855), the first of his novels to achieve success, was succeeded by the sequence of ‘Barsetshire’ novels, Barchester Towers (1857), Doctor Thorne (1858), Framely Parsonage (1861), The Small House at Allington (1864) and The Last Chronicle of Barset (1867). This series, regarded by some as Trollope’s masterpiece, demonstrates his imaginative grasp of the great preoccupation of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English novels – property – and includes a gallery of recurring characters, including, among others, Archdeacon Grantly, the worldly cleric, the immortal Mrs Proudie and the saintly warden, Septimus Harding. Almost equally popular were the six Palliser novels comprising Can You Forgive Her? (1864), Phineas Finn (1869), The Eustace Diamonds (1873), Phineas Redux (1874), The Prime Minister (1876) and The Duke’s Children (1880).

JULLIAN THOMPSON was educated at Hertford College, Oxford, where he currently holds a lectureship. He is also lecturer in English at Regent’s Park College, Oxford. He has edited Anthony Trollope’s Ayala’s Angel and Cousin Henry for Oxford World’s Classics series.

ANTHONY TROLLOPE

The Small House at Allington

Edited with an Introduction and Notes by

JULIAN THOMPSON

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published 1864

Published in Penguin Classics 1991

Reprinted with a Chronology 2005

Introduction and notes copyright © Julian Thompson, 1991

All rights reserved

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject

to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent,

re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s

prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in

which it is published and without a similar condition including this

condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978–0–141–90548–8

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I SHOULD like to thank my wife Catherine

for help with the preparation of this edition.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Chronology

A Note on the Text

Suggestions for Further Reading

A Map of Allington

THE SMALL HOUSE AT ALLINGTON

Appendices

Notes

INTRODUCTION

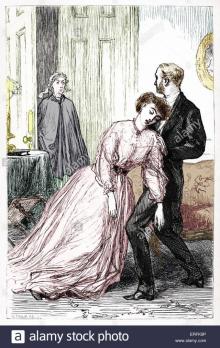

WHEN TROLLOPE wrote The Small House at Allington for the Cornhill Magazine, he was approaching the height of his popularity and earning power. It was a sequel to Framley Parsonage, with which he had established his own name and, in a sense, that of the magazine. It also atoned for the flashy and grotesque The Struggles of Brown, Jones and Robinson, which had just finished its Cornhill run, and constituted, in Trollope’s view, the ‘hardest bargain which I ever sold to a publisher’. The Small House brought him £3000 – less than half what George Eliot got for Romola’s serialization in the Cornhill, but his highest outright fee to date. More significantly (appearing with Millais’s thoughtful and accessible illustrations), it brought him the kind of popular obsession with the life of his characters reserved in his day for Dickens and in ours for soap-opera. Lily Dale’s personality and predicament particularly fascinated Trollope’s readers (David Skilton has discovered that at least two ships were named after her in the 1860s.)1. The Illustrated London News declared ‘flesh and blood cannot endure’ that ‘one of the most charming creations that ever author devised’ should be ‘sentenced to the life of a widowed maid’. There was ‘as much speculation’, commented the Athenaeum reviewer, ‘whether Lily would marry Johnny Earnes as about any “marriage on the tapis”… in any town or village in Great Britain’. The Spectator reviewer assumed her story was ‘too well known’ to need to repeat its details.2 Letters arrived, and kept coming down the years, beseeching Trollope to marry off Lily to her deserving suitor, or at least to pay Lily and Johnny the compliment of a sequel. Critical reception of the novel was among the most favourable Trollope ever received, with the De Courcys, Squire Dale, Lily, Bell and Crosbie all single out for special praise.

In more recent times, critical opinion has been less enchanted with the book, although there is little uniformity in the complaints which have been made. Professor James Kincaid, perhaps the most influential of modern Trollopians, is troubled by what he calls its ‘darkness’, its failure to adhere to ‘comic form’,3 and R. C. Terry has called it the ‘blackest of the Barsetshire novels’.4 V. S. Pritchett and J. B. Priestley, however, see it as an undisturbing and unevenful book, a quintessential ‘escapist’ Trollope novel, one of the unofficial ‘air raid shelters’ of the Second World War.5 Bradford Booth, doyen of the first post-war generation of Trollope academics, sounds simply bored:

The Small House is probably the weakes link in the [Barsetshire] chain. There is a want of force, a lack of spark, in this slow-paced narrative; in consequence, there are a number of heavy chapters that can only be described as dull. This is the judgement that one must render against the whole Lily Dale–Crosbie romance.6

At first glance this chorus of disillusion is difficult to explain. Part of the trouble, of course, is the novel’s dubious relationship with the remainder of the Barchester Chronicle (apart from Barsetshrie interludes in Chapters 16 and 55 the action is laid either in London or in the adjoining country). Ronald Knox, that formidable cartographer of the forty-first English county, was never reconciled to The Small House, and Trollope himself kept it out of the sequence when he listed the Barchester novels in An Autobiography with a view to ‘combined republication’. When, in 1878, such an edition appeared, The Small House kept its place only on the remonstration of the publishers, Chapman & Hall. Yet, if the book has only adventitious interest for the Barsetophile, that is no excuse for undervaluing it. In many ways The Small House gains by comparison with the less mature Barchester books Trollope wrote in the 1850s. It is demonstrably a novel of greater psychological ambition than The Warden, more assured narrative tone than Barchester Towers, and does not warp like Dr Thorne under a mechanically imposed plot. If it falls short of the comprehensiveness of The Last Chronicle of Barest it has no stretches as arid and redundant as the ‘Jael and Sisera’ sub-plot in that novel, and Johnny Eames’s metropolitan ‘dissipations’ in The Last Chronicle seem

more etiolated and pretentious than his dealings with Amelia Roper in The Small House.

Though The Small House at Allington was composed rapidly and under some pressure (see A Note on the Text), and Trollope admitted that he had ‘created better plots’, there is little evidence of hasty writing. Development is leisurely and the multi-plot structure unfolds with more than customary Trollopian expansiveness, but it is not clear where (occasionally in Burton Crescent, perhaps?) interest is supposed to flag. Nor is it easy to see why the novel is considered especially dark. Eames’s disappointment, Crosbie’s marital shipwreck and Lily’s psychological convolutions are handled seriously rather than portentously. The Spectator reviewer (Richard Holt Hutton) struck the right note when he spoke of an ‘admirable representation of our modern social world, with its special temptations, special vices, and special kinds of retribution’.7

Pre-eminently, in any defence of the novel, there is Lily Dale. Where Victorian readers found her compelling, modern critics have followed Trollope’s lead in An Autobiography in finding her exasperating; some have gone beyond him, in finding her tiresome. This is mere pique. Lily is a very lively heroine, filling the scenes in which she appears with judicious banter. She jokes about the ‘savagery’ of doctors, displays an unheroineish appetite for ‘mutton chops’, and is ‘gay, bright and wedding-like’ at her sister’s marriage. Nor is there anything hysterical about her humour, though occasionally, as when she descants on the maddeningly repetitive wallpaper pattern of her bedroom, it suggests an underpinning malaise. As Stephen Wall has commented, ‘Instantly recognisable, she remains a mystery.’8 No convenient formula of sexual frustration or apprehension (Lawrence Lerner opines that ‘she will not marry John because she is frightened of sex’9) will encapsulate her complex psychological predicament. Trollope (who lived with her obstinacy through the sequel, The Last Chronicle of Barset) called her a ‘female prig’ (‘French prig’ in some older copies of An Autobiography is a misreading of Trollope’s manuscript). His verdict is harsh; but it certainly doesn’t signal authorial malevolence, even without the knowledge that Trollope considered Thackeray’s Henry Esmond the finest novel in the lanugage, despite the ‘priggish’ qualities of its central figure. The psychological investigation of priggishness, pace Trollope, has produced finer studies than Thackeray’s Esmond: Clym Yeobright in Hardy’s The Return of the Native, for instance, or Fanny Price in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. Lily is much more lively than then taciturn Fanny, but, as with Fanny, it is not her intransigent idealism that alienates readers, but her ultimate inacessibility. Lily, despite her relish for flirting with the aged Earl De Guest, or becoming a heroine to the irascible Hopkins (neither of them sexually eligible), is formidably self-contained. She has no father, and no significant memory of him. Her mother has no practical hold over her (Lily jokes about her own domestic ‘tyranny’) and her elder sister Bell, though devoted, is prone to bouts of unreachable self-communion regarding her own love-life at crucial junctures in the novel. Trollope spends a paragraph or so sketching in the hereditary ‘spice of obstinacy’ in the Dales; but there is no significant examination of Lily’s childhood or belongings to account for her extraordinary attitude to love and her lovers, albeit she sometimes tries to mask it with a conventional novelettish idealism. Lily devotes herself to Crosbie with all the solemnity of Gospel phraseology (‘I shall love you with all my heart and all my strength’), but with disturbing rapidity: it takes a few flirtatious games of croquet and a suspiciously grandiloquent moonlit autumn walk. Her first view of Crosbie, given with bright penetrative gusto, is as a kind of snobbish – albeit ‘ducky’ – ‘Phoebus Apollo’:

‘I’ll tell you what he is, Bell; Mr Crosbie is a swell.’ And Lilian Dale was right; Mr Crosbie was a swell.

Crosbie is a man of superficially overbearing energy and elegance with, at least we judge him early in the novel, a good deal of moral growing up to do. His friends are social conveniences, the Civil Service a gymnasium for his ego. Lily deciphers his pushiness and empty raciness (‘I fancy I do like slang. I think it’s awfully jolly to talk about things being jolly’); and then, almost as though she desired and deserved to be disappointed, investes her soul in him. ‘It was all my own fault, as I had seen it from the first’, she comments later in the novel. Her badinage after she accepts him invests him with a significance he cannot possibly live up to. When Mrs Dale conventionally wonders if he is good enough for her daughter, Lily teaches her that she ‘must think him good enough for anything’. Lily, we hear much later, prefers novels to real life (though she is discerning enough to reject the silly ones she has at Allington), for ‘real life sometimes is so painful’. Her attitude to feminine devotion is troublingly theoretic:

She had an idea of her own, that as a girl should never show any preference for a man till circumstances should have fully entitled him to such manifestation, so also should she make to drawback on her love, but pour it forth for his benefit with all her strength, when such circumstances had come to exist.

Crosbie is this subjected to an automatic torrent of affection, given with an openness that distresses his calculating heart, and which curiously divorces the reader’s attention, as Lily seems herself to be divorced, from the nature of its recipient. ‘All devotion is rather the fruit of the mental gifts of the admirer than the desert of the adored,’ pointed out the critic for the Saturday Review.10 This is extensively illustrated in the long-remembered moonlit walk beside the Allington churchyard:

‘Don’t you like the moon?’ she said, as the took his arm, to which she was now so accustomed that she hardly thought of it as she took it.

‘Like the moon? – well; I fancy I likt the sun better. I don’t quite believe in moonlight. I think it does best to talk about when one wants to be sentimental.’

‘Ah; that is just what I fear. That is what I say to Bell when I tell her that romance will fade as the roses do. And then I shall have to learn that prose is more serviceable than poetry, and that the mind is better than the heart, and – and that money is better than love. It’s all coming, I know; and yet I do like the moonlight.’

‘And the poetry – and the love.’

‘Yes. The poetry much, and the love more. To be loved by you is sweeter even than any of my dreams – is better than all the poetry I have read.’

‘Dearest Lily,’ and his unchecked arm stole round her waist.

‘It is the meaning of the moonlight, and the essence of the poetry,’ continued the impassioned girl. ‘I did not know then why I liked such things, but now I know. It was because I longed to be loved.’

‘And to love.’

‘Oh, yes. I would be nothing without that. But that, you know, is your delight – or should be. The other is mine. And yet it is a delight to love you; to know that I may love you.’

‘You mean that this is the realization of your romance.’

‘Yes; but it must not be the end of it, Adolphus. You must like the soft twilight, and the long evenings when we shall be alone; and you must read to me the books I love, and you must not teach me to think that the world is hard, and dry, and cruel – not yet. I tell Bell so very often; but you must not say so to me.’

‘It shall not be dry and cruel, if I can prevent it.’

‘You understand what I mean, dearest. I will not think it dry and cruel, even though sorrow should come upon us, if you – I think you know what I mean.’

‘If I am good to you.’

‘I am not afraid of that – I am not the least afraid of that. You do not think that I could ever distrust you? But you must not be ashamed to look at the moonlight, and to read poetry, and to –’

‘To talk nonsense, you mean.’

But as he said it, he pressed her closer to his side, and his tone was pleasant to her.

‘I suppose I’m talking nonsence now?’ she said, pouting. ‘You liked me better when I was talking about the pigs; didn’t you?’

‘No; I like you best now.’

‘And why didn’t you like me then? Did I say anything to offend you?’

‘I like you best now, because –’

They were standing in the narrow pathway of the gate leading from the bridge into the gardens of the Great House, and the shadow of the thick-spreading laurels was around them. But the moonlight still pierced brightly though the little avenue, and, she, as she looked up to him, could see the form of his face and the loving softenss of his eye.

‘Because –’ said he; and then he stooped over her and pressed her closely, while she put up her lips to his, standing on tip-toe that she might reach to his face.

‘Oh, my love!’ she said. ‘My love! my love!’

Stephen Wall has recently offered a brilliant analysis of the importance of this passage, claiming that ‘the implications of what Lily says in this scene far outstrip any authorial explanation of her personality that has so far been given’.11 The decorous but demonstrative sexuality that marks Crosbie’s replies is genuine; his juvenile lead persiflage rather perfunctory. Crosbie’s patronizing ways probably do not prevent him from receiving Lily’s emotional articulacy with pleasure, but there is no sense that he understands how extraordinary it is. Lily’s conviction that ‘romance will fade as the roses do’, that the moment of sentimental tryst is fleetingly self-contained, sounds prophetic rather than conventional, and her careful demarcation of roles (a lover’s delight is to be loved rather than to love) suggests that, for her, human affection is a disturbingly hermetic business (Bell Dale, too, is prone to such exquisite introspections, as the firelit scene where she luxuriates in Dr Crofts’ proposal, but does not give him an answer, demonstrates). The landscape of her love and is pleasures (reading in the long evenings) is silvery, twilit, autumnal; her appropriation of Crosbie’s sensibility uncompromising, so that he must love without discrimination the ‘nonsense’ of her poetry, and her nonsense about the pigs. At the end of the scene she strains into his embrace with an abandonment that suggests the ‘impurdence’ Tollope pointed out in private correspondence to one of Lily’s admirers,12 and stresses keenly enough in his narrative voice: ‘she had resolved to trust in everything, and, having so trusted, she would not provide for herself any possibility of retreat.’

Doctor Thorne

Doctor Thorne Can You Forgive Her?

Can You Forgive Her? The Last Chronicle of Barset

The Last Chronicle of Barset The Fixed Period

The Fixed Period Phineas Redux

Phineas Redux The Way We Live Now

The Way We Live Now Castle Richmond

Castle Richmond The Bertrams

The Bertrams An Old Man's Love

An Old Man's Love The Belton Estate

The Belton Estate Marion Fay: A Novel

Marion Fay: A Novel The Claverings

The Claverings The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson

The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson Nina Balatka

Nina Balatka The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp

The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp Barchester Towers cob-2

Barchester Towers cob-2 The Chronicles of Barsetshire

The Chronicles of Barsetshire The Warden cob-1

The Warden cob-1 Framley Parsonage

Framley Parsonage Christmas at Thompson Hall

Christmas at Thompson Hall The Warden

The Warden The Palliser Novels

The Palliser Novels The Small House at Allington

The Small House at Allington Barchester Towers

Barchester Towers The Small House at Allington cob-5

The Small House at Allington cob-5 The Duke's Children

The Duke's Children Phineas Finn, the Irish Member

Phineas Finn, the Irish Member Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope