- Home

- Anthony Trollope

The Duke's Children

The Duke's Children Read online

THE DUKE'S CHILDREN

ANTHONY TROLLOPE was born in London in 1815 and died in 1882. His father was a barrister who went bankrupt and the family was maintained by his mother, Frances, who was a well-known writer. His education was disjointed and his childhood generally seems to have been an unhappy one.

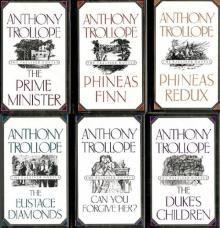

Trollope enjoyed considerable acclaim as a novelist during his lifetime, publishing over forty novels and many short stories, at the same time following a notable career as a senior civil servant in the Post Office. The Warden (1855), the first of his novels to achieve success, was succeeded by the sequence of ‘Barsetshire’ novels, Barchester Towers (1857), Doctor Thorne (1858), Framley Parsonage (1861), The Small House at Allington (1864) and The Last Chronicle of Barset (1867). This series, regarded by some as Trollope's masterpiece, demonstrates his imaginative grasp of the great preoccupation of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English novels – property – and features a gallery of recurring characters, including, among others, Archdeacon Grantly, the worldly cleric, the immortal Mrs Proudie and the saintly warden, Septimus Harding. Almost equally popular were the six brilliant Palliser novels comprising Can You Forgive Her? (1864), Phineas Finn (1869), The Eustace Diamonds (1873), Phineas Redux (1874), The Prime Minister (1876) and The Duke's Children (1880). Among his other novels are He Knew He Was Right (1869) and The Way We Live Now (1875), each regarded by some as among the greatest of nineteenth-century fiction.

DINAH BIRCH was educated at St Hugh's College, Oxford, and was a Junior Research Fellow at Merton College, Oxford. She subsequently taught at St Hugh's College, and at the Open University. Since 1990 she has been Fellow and Tutor in English at Trinity College, Oxford, and Lecturer in English at the University of Oxford. Her publications include Ruskin's Myths (1988) and Ruskin on Turner (1990).

ANTHONY TROLLOPE

THE DUKE'S CHILDREN

EDITED WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND

NOTES BY DINAH BIRCH

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published 1880

Published in Penguin Classics 1995

10

Introduction and notes copyright © Dinah Birch, 1995

All rights reserved

The moral right of the editor has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-193243-9

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

FURTHER READING

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

THE DUKE'S CHILDREN

A NOTE ON THE MANUSCRIPT

NOTES

INTRODUCTION

The Duke's Children, last of the six Palliser novels, closes the long story of the Duke of Omnium. It was written in 1876, when Trollope was sixty-one years old – still in the full flow of his astonishing productivity, but beginning to see his public success decline. The Duke's previous appearance in The Prime Minister, published in four volumes in 1876, had not been well received. Trollope decided not to publish The Duke's Children immediately. He could well afford to wait, for this was a time when he was writing more than publishers and readers could easily cope with. Six novels appeared in quick succession after The Prime Minister, together with two volumes of travel writing and an affectionately commemorative biography of Thackeray. In this obsessive diligence, as in many other traits, Trollope resembles his fictional Duke. He could never thrive without work. His late novels, including The Duke's Children, persistently brood over the difficulties that men and women stumble over in their efforts to find and keep the right work.

When The Duke's Children finally appeared, Trollope had cut it to fit the space allocated by Charles Dickens (son of the novelist) in All the Year Round (4 October 1879 to 24 July 1880). This is the version that Chapman and Hall published in three volumes in 1880. Those who first read it can hardly have done so without some previous knowledge of Trollope's most famous nobleman. Forgetting their recent lamentations over Trollope's alleged decline, critics generally gave a benign welcome to this last episode in the Duke's extended fictional life – ‘the only duke whom all of us know’, as the Westminster Review appreciatively remarked. The parliamentary novels, as Trollope calls them, trace the history of figures associated with Plantagenet Palliser, seen first as an ambitious young Liberal politician, then Duke of Omnium and for a time Prime Minister of England. The opening sentence of The Duke's Children speaks with companionable ease of ‘our old friend, the Duke of Omnium’, and the narrative that follows is resonant with the remembered history of a man who had come to be more than a fiction to Trollope – ‘so much do I love the man whose character I had endeavoured to portray’ (An Autobiography, 1883, Chapter 20).

The wit and acumen of the Duke's wife, Glencora, had contributed much to the success of the parliamentary series. But this novel audaciously begins by expunging what might have seemed its central asset. Glencora is dead, and the austere Duke widowed and desolate. He is left with the responsibility of three wilful children about to embark on adult lives, apparently with little of the high principle and constant discipline which had guided the Duke's own private and political career. His only daughter, Lady Mary, confounds her father by calmly defying his dearest wishes. His two feckless sons, Lord Silverbridge and Lord Gerald, are sent down from university in disgrace, run up gambling debts of breathtaking dimensions, and seem incapable of responsible thought or action. Throughout The Duke's Children, Palliser watches the choices his unruly progeny make with dismay, and ineffectively tries to make their lives conform to the measured patterns of his own.

Of all the many late developers in Trollope's fiction, Palliser is the most impressive. He is a pale and unprepossessing figure when first introduced in The Small House at Allington (1864): ‘He was a thin-minded, plodding, respectable man, willing to devote all his youth to work, in order that in old age he might be allowed to sit among the Councillors of the State’ (Chapter 23). Matured by political and marital vicissitudes, Palliser gains in stature until, at the height of his authority in The Prime Minister, he comes to embody the ‘perfect gentleman. If he be not, then am I unable to describe a gentleman’ (An Autobiography, Chapter 20). For Trollope no finer ideal exists. Yet much in Palliser's life denies what was generally conceived as the ideal of a gentleman. The Duke is socially awkward, and has no time for gentlemanly pursuits like hunting or shooting. His unremittingly single-minded devotion to his work challenges the notion of a gentleman's leisure. Trollope could not be satisfied with one side of a question. In The Duke's Children, he sets out to expose deep flaws in this ‘perfect gentleman’. Through his inept and baffled dealings with his children, the deficiencies of the Duk

e are unsparingly revealed. For all his integrity, Palliser has a proud and limited nature. The limitations are pitied, but the pride is seen to be culpable and potentially destructive.

The first pages of the novel dwell extensively on the Duke's multiple inadequacies. He has failed to benefit from the European travel which had preceded his wife's death; he is stricken and helpless in her absence; he is unable to make real contact with his remaining family; he is stiff, haughty and prematurely old. When it emerges that his daughter, Lady Mary, has engaged herself to marry Francis Tregear, the impecunious young friend of her brother, the Duke is devastated. What makes the discovery much worse is the revelation that his wife had encouraged this love match. Without the resources of her quick sympathy, the Duke can scarcely deal with the consequences of her rashness.

The Duke's intransigent opposition to the proposed marriage between Francis Tregear and Lady Mary is one of the many points at which the book looks back over the vistas of history accumulated in the Palliser novels. Like her daughter, Glencora Palliser had also made an early commitment to a man with beauty (always a bad sign in the fictions of this homely novelist – Tregear is ‘beautiful as Apollo’, p. 31) – and little money. Her disapproving family and friends had persuaded her to accept young Palliser instead of the rakish Burgo Fitzgerald, but the Duke had persistently felt that Glencora's strongest and most spontaneous affections had been irrevocably bestowed elsewhere. Now, through his wife's impulsive encouragement, it seemed that this story of a destructive early love was to repeat itself. Palliser at first believes that his repudiation of the aspiring Tregear is in the interests of social order and justice, and of Lady Mary herself. In a difficult but necessary acquisition of self-knowledge which amounts to his final act of moral heroism, the Duke comes to understand that his antipathy is in fact driven by his own emotional needs. Learning about himself enables him to recognise others. Lady Mary had been no more than a pretty toy to him – ‘the most charming plaything in the world on the few occasions in which he had allowed himself to play. But as to her actual disposition, he had never taken any trouble to inform himself’ (p. 151). He had not taken her seriously. Many of Trollope's fictional fathers find that their quiet daughters are more determined than anyone had bargained for. For the Duke, it is a profound but salutary shock to find himself weaker than his daughter.

In the parallel story of the Duke's eldest son, Silverbridge, who inflicts a double wound on his father by entering Parliament as a Conservative rather than a Liberal and then deciding to marry Isabel Boncassen, ‘the granddaughter of an American day-labourer’ (p. 414), rather than the aristocratic Lady Mabel Grex, we see Palliser's wishes frustrated again. He is powerless to prevent Silverbridge getting what he wants. The Duke is capable, immensely wealthy and tenacious, but he has grown old. In shaping the concluding episodes of Palliser's life, the ageing Trollope acknowledges the unstoppable precedence of youth.

Yet The Duke's Children remains a comedy, beginning with a death and ending with marriages. For all its sobriety, it is among the most optimistic of Trollope's novels. The Duke is thwarted, but he is also educated, and his story reflects Trollope's faith that parents can and should learn from their inheritors. His family is restored to him, together with a new understanding of ‘how necessary it was that he should have someone who would love him’ (p. 421). Even his work is restored to him, though it too has to be accommodated to new circumstances. At the end of the novel he has become President of the Council in a new Liberal administration. Relinquishing the pride and power of high office, Palliser is rewarded with work proper to his nature. The young have their own lessons to learn, but in this novel they emerge as fixed and relatively thin creations beside their elders. It is the old who have sustained histories of complexity and suffering, with more suffering, and more growth, in store for them. For all his grand principles, the Duke has been living in a moral muddle. The Liberal creed which he proclaims rests on the assertion of human equality. Without knowing that his son intends to marry her, the Duke expounds his beliefs to Isabel Boncassen: ‘There is no greater mistake than to suppose that inferiority of birth is a barrier to success in this country’ (p. 310). This is a theory that the Duke has never been able to reconcile with ‘his own pride of race and name’ (p. 311), and he is aghast when his eldest son and only daughter both propose to marry out of the nobility. What rescues him from a stubborn pride in his public position is the strength of his private affections. Undemonstrative and remorselessly formal, the Duke is repeatedly shown to be the most loving character in the novel. He cannot bear to see the distress of his children, though he attempts to persuade himself that it is his duty to do so. The pathos of the Duke's incapacity to express his deepest feelings is touchingly drawn. He gets closest to openness with Silverbridge. Invited to dine with his son at his club, the Duke's habit of reserve begins to melt: ‘Then the father looked round the room furtively, and seeing that the door was shut, and that they were assuredly alone, he put out his hand and gently stroked the young man's hair. It was almost a caress, – as though he would have said to himself, “Were he my daughter, I would kiss him”’ (p. 168). It is a moment hedged about with qualifications – ‘almost a caress’, ‘as though he would have said’, ‘were he my daughter’. Yet it is in the Duke's terms a momentous emotional surrender.

But Silverbridge is not a daughter. He is a son, and as such he is himself encompassed by the codes of acceptable masculine behaviour that so restrict the Duke's emotional life. In The Duke's Children, Trollope considers the price exacted by such codes. This was not a new theme for him. Perhaps remembering his own sad father, he had repeatedly created versions of the lonely old man whose thoughts, like those of the testy Squire Dale of The Small House at Allington, ‘were ever gentler than his words’ (Chapter 38). Archdeacon Grantly, who bosses and blusters his way through the pages of the Barsetshire novels, is among the liveliest of such portraits. In his final fictional appearance (The Last Chronicle of Barset, published in 1867), the bluff Archdeacon almost allows intransigent pride to separate him from the grown-up son he loves dearly. Like the Duke, he does so because he is convinced that his son is marrying beneath him. However, the Archdeacon is luckier than the Duke in having a sensible wife who can stave off the worst results of his unbending foolishness. The Duke had needed Glencora, who like so many of Trollope's fictional wives was more forceful than her husband. She ‘had been essentially human, had been a link between him and the world’ (p. 3). Without that link, he feels – and almost becomes – lost.

The Duke's long story might have ended in tragedy – or in farce. His uncomprehending obstinacy often provides the novel with a rueful comedy, as Trollope records his bouts of frustrated ‘wailing’ in the face of his children's perverse persistence. The fact that he is finally allowed to retain his dignity in full measure, together with as much happiness as his stern nature could hope to accommodate, represents the element of wish-fulfilling fantasy which the apparently realist fiction of Trollope always contains. This is the novel that Trollope began immediately after he had finished his retrospective An Autobiography (published posthumously) in the spring of 1876, and it is a continuation of that attempt to write a successful life for himself. In its caustic condemnation of greed and hypocrisy, it shares many of the preoccupations of preceding major novels of the 1870s, like The Way We Live Now (1875) and The American Senator (1877). But it is not, as they are, a ‘condition-of-England’ novel. This is a novel in which Trollope is thinking about his own life. Like the Duke, he had two sons who were not finding it easy to settle, having noticeably omitted to inherit their father's habits of unceasing industry: ‘How completely had he failed to indoctrinate his children with the ideas by which his own mind was fortified and controlled!’ (p. 413). The Duke is by no means an image of Trollope. He is much less intelligent, and more ascetic. But his paternal position is comparable. In constructing this narrative of reconciliation and redemption, in which family loyalty and good nature (neithe

r of the Duke's boys is really a bad lot) is at last rewarded, Trollope defends himself against the fear that his own story might have a different ending.

In Trollope's fictional lives, the recalcitrant tangles of his experience are smoothed into something approaching order. But this equanimity is not created without cost, and The Duke's Children acknowledges discordant notes. The theme of age and its defeats is not confined to Trollope's treatment of the Duke and his troubles. It pervades the novel. Curiously, it finds its most sombre expression in a character who is distinctly young in years. Lady Mabel Grex, who fails in her bid to be the next Duchess of Omnium, is twenty-two years old. She is clever, beautiful and firm of mind. Yet she feels herself to be too old to succeed. She has a great deal – too much – already behind her. Her story begins, as Trollope insistently reminds us, ‘in medias res’ (p. 55). Mabel has the noble blood which the Duke values so highly, but the ancient aristocracy she represents is exhausted and corrupt, with a ‘blasé used-up way of life of which Lady Mabel was conscious herself’ (p. 271). The men in her family are characterised by a casually vicious brutality that is a reminder of how far Trollope was from an unreasoned respect for high breeding. Juliet McMaster has noted how deeply Mabel herself is damaged by her identification with a romantic retrospect that has become sterile.* Grex, the family home she venerates, has been ruined by the careless self-indulgence of her ancestors, and is now a Byronically gloomy pile which represents, with an almost Gothic intensity unusual in Trollope, her spent condition. Northern landscapes repeatedly suggest desolation and emotional defeat in Trollope's fictional geography, and the rocks and black water surrounding the old brick walls of Grex haunt Mabel's hopeless story. Silverbridge is half-committed to her edgy sophistication, but finally prefers the buoyant energy embodied in the rival attractions of the very much more wholesome Isabel Boncassen. In choosing the American, Silverbridge chooses youth, and the novel commends the wisdom of his decision.

Doctor Thorne

Doctor Thorne Can You Forgive Her?

Can You Forgive Her? The Last Chronicle of Barset

The Last Chronicle of Barset The Fixed Period

The Fixed Period Phineas Redux

Phineas Redux The Way We Live Now

The Way We Live Now Castle Richmond

Castle Richmond The Bertrams

The Bertrams An Old Man's Love

An Old Man's Love The Belton Estate

The Belton Estate Marion Fay: A Novel

Marion Fay: A Novel The Claverings

The Claverings The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson

The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson Nina Balatka

Nina Balatka The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp

The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp Barchester Towers cob-2

Barchester Towers cob-2 The Chronicles of Barsetshire

The Chronicles of Barsetshire The Warden cob-1

The Warden cob-1 Framley Parsonage

Framley Parsonage Christmas at Thompson Hall

Christmas at Thompson Hall The Warden

The Warden The Palliser Novels

The Palliser Novels The Small House at Allington

The Small House at Allington Barchester Towers

Barchester Towers The Small House at Allington cob-5

The Small House at Allington cob-5 The Duke's Children

The Duke's Children Phineas Finn, the Irish Member

Phineas Finn, the Irish Member Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope