- Home

- Anthony Trollope

Phineas Finn, the Irish Member

Phineas Finn, the Irish Member Read online

PHINEAS FINN

ANTHONY TROLLOPE was born in London in 1815 and died in 1882. His father was a barrister who went bankrupt and the family was maintained by his mother, Frances, who was a well-known writer. He received little education and his childhood generally seems to have been an unhappy one.

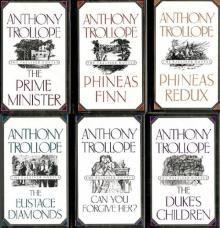

Happily established in a successful career in the Post Office (from which he retired in 1867), Trollope's first novel was published in 1847. He went on to write over forty novels as well as short stories, and enjoyed considerable acclaim as a novelist during his lifetime. The idea for The Warden (1855), the first of his novels to achieve success, was conceived while he wandered around Salisbury Cathedral one midsummer evening. It was succeeded by other ‘Barsetshire’ novels employing the same characters including Archdeacon Grantly, the worldly cleric, the immortal Mrs Proudie and the saintly warden, among others. These novels are Barchester Towers (1857), Doctor Thorne (1858), Framley Parsonage (1861), The Small House at Allington (1864), and The Last Chronicle of Barset (1867). This series is regarded by many as Trollope's masterpiece in which he demonstrates his imaginative grasp of the great preoccupation of eighteenth and nineteenth century English novels – property. Almost equally popular were the six brilliant Palliser novels comprising Can You Forgive Her? (1864), Phineas Finn (1869), The Eustace Diamonds (1873), Phineas Redux (1874), The Prime Minister (1876) and The Duke's Children (1880).

JOHN SUTHERLAND, who has edited Anthony Trollope's The Eustace Diamonds and William Thackeray's The History of Henry Esmond for Penguin, is a Professor of English at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. His other publications include Fiction and the Fiction Industry and Best Sellers: Popular Fiction of the 1970s.

Anthony Trollope

PHINEAS FINN,

THE IRISH MEMBER

Edited with an introduction

by John Sutherland

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Books USA Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, 182–190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published 1869

Published in The Penguin English Library 1972

Reprinted in Penguin Classics 1985

22

Introduction and Notes copyright © John Sutherland, 1972

All rights reserved

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN 978-0-14-193242-2

Contents

Introduction

Bibliography

The Background to Phineas Finn

A Note on the Text

PHINEAS FINN

Appendix A: Trollope's Political Creed

Appendix B: A Note on the Manuscript

Notes

Introduction

I

‘COMFORTABLE, but not splendid’ was how the aged Trollope summed up his literary achievement. Sums in fact are very prominent in this final reckoning and Phineas Finn is seen to have contributed generously to the novelist's comforts. In the aggressively indiscreet list of earnings presented at the end of the Autobiography this one work is credited with fetching £3,200, a handsome enough reward by our standards, magnificent by Victorian. Phineas Finn marks the second highest peak in Trollope's literary earnings; more profitably to its readers it also marks a distinct change in the literary formula which had to date netted him close on £30,000. Change was due. By the time he came to write Phineas Finn Trollope had, novel for novel, outwritten Dickens by two and Thackeray by four to one: worse than this he had repeated himself. Facetious reviewers were already speculating about the size of the British Museum and, more seriously, insinuating that English letters would be not a whit the poorer if Mr Trollope never blotted another line. But if he had run through one career as a novelist, Trollope (motto: nulla dies sine linea) was quite prepared to set off on another. His energy was marvellous, his diligence legendary, and hostile criticism though it might modify could not extinguish his urge to write. Indeed it probably stimulated him to necessary creative efforts: the nature of the stimulus is suggested by the famous story he tells against himself, in the Autobiography, of a club conversation between two clergymen overheard in 1865:

They soon began to abuse what they were reading, and each was reading some part of some novel of mine. The gravamen of their complaint lay in the fact that I reintroduced the same characters so often! ‘Here,’ said one, ‘is that archdeacon whom we have had in every novel he has ever written.’ ‘And here,’ said the other, ‘is the old duke whom he has talked about till everybody is tired of him. If I could not invent new characters, I would not write novels at all.’ Then one of them fell foul of Mrs Proudie. It was impossible for me not to hear their words, and almost impossible to hear them and be quiet. I got up, and standing between them I acknowledged myself to be the culprit. ‘As to Mrs Proudie,’ I said, ‘I will go home and kill her before the week is over.’ And so I did. (Chapter 15.)

It is well told: we hear the robust self-mockery through the print and detect the disguised artistic sensitivity. But more to the point here is how Trollope reacts. He does not for a moment contemplate, as his unconscious critic would have him, giving up novels altogether. Instead he is spurred to write something different, at once and with apparently unimpaired vigour.

The immediate outcome of the above encounter was the killing of Mrs Proudie, Trollope's finest dragon, in chapter 66 of The Last Chronicle of Barset. A more important termination is that implied in the novel's title. Not that it should be imagined all this came from one unlucky conversation. Trollope did not have to eavesdrop to gather that the public was sated and inclined to be rude about his novels. His club journals would tell him as much. The reviewer of Phineas Finn's predecessor, The Belton Estate (1866), who declared it ‘insufferably tiresome and absurd’ that Mr Trollope should once again write the same old novel was public enough and, unfortunately, typical enough for Trollope, who conscientiously heeded criticism, to know how he stood.

The reviewer could not have known that as he wrote them his objections were being met. The Belton Estate (an unexciting tale of love and property) marks time at the end of Trollope's great Barsetshire chronicles and the getting under way of his Palliser series, sometimes, but not by Trollope, called ‘the political novels’. One says getting under way rather than launching: for, although the author himself records that with Phineas Finn ‘I commenced a series of semi-political tales’, an earlier false start is evident in Can You Forgive Her? (1864). This forerunner introduces the first portrait at length of Plantagenet Palliser as well as the magnified concerns of the second series. Can You Forgive Her? moves between the big metropolitan world of politics – ‘the saloons of the mighty’ (Disraeli's slightly absurd term; we should probably use the equally absurd sociologism ‘power élite’) and the familiar squirearchical setting where twenty-pound notes are more important than reform acts, small livings than cabinet places. There are respectable critics who talk of a ‘Phineas Finn series’ beginning with our novel,

but Can You Forgive Her? is usually taken as the prelude to a more comprehensive Palliser group: Phineas Finn (1868), The Eustace Diamonds (1873), Phineas Redux (1874), The Prime Minister (1876), and The Duke's Children. (1880).

Together these six interpenetrating novels, each long in its own right, make up a composition which is huge and coherent: coherent in a way that the huge Barsetshire chronicles are not, for there Trollope seems to have had neither master-plan nor over-arching time scheme, whereas in starting Phineas Finn he held ‘constantly before me the necessity of progression in character – of marking the changes in men and women which would naturally be produced by the lapse of years’. Change, progression (with the accent on progress) and lapse of years: these, if anything, indicate Trollope's grand endeavour in the Palliser novels. And it is not merely the psychological changes wrought in character by time which occupy him; an extended analysis of politically controlled change is as much his concern. The Barsetshire Trollope, although fascinated by such change, tended to respond emotionally to it as an irritating upset of what would run very well if left alone. He takes side with the Grantlys, Hardings and Tory squires in their resentment against a central governing body whose reform means meddling and muddling: ‘I want no change,’ says Mr Harding, and in the story of Hiram's Hospital or the replacement of Grantlys by Proudies in cathedral palaces he speaks for his author. The Palliser Trollope with his wide social and inner-political perspective is as much the historian as the story-teller. Over the vast expanse of the Palliser series is a rich surface of documentary record, the fashions, slang, manners and politics of twenty years. But more than this the sense of era, of a historical narrative inevitably moving and underlying all the human narratives, is wonderfully achieved.

‘If only he would not write so much!’ The objection to Trollope made in 1870 is commonplace. But it was, as Charles Reade stressed, ‘a GIGANTIC age’ and many of its achievements are to scale. Admittedly Trollope does not always handle bulk gracefully; at times the series resembles Aristotle's 1,000-mile-long animal which has no form because it has too much mass. And in Phineas Finn he is especially guilty of falling into that shapelessness which comes from making endings new beginnings. The last-page marriage in which the hero returns to Ireland and his first love would work if Phineas, Mary and the little Finns could be left in the vagueness of the ‘happily ever after’. But when ‘after’ has to be specified in Phineas Redux some brutal rearrangement is necessary; harmless Mary and her child are killed to release the hero for new adventures: it is a revision Trollope himself felt painful. Phineas Finn whole novel, Phineas Finn half-novel with its sequel, Phineas Finn one-sixth novel in a series are not satisfactorily reconciled and in general the links between the Palliser novels are capricious (partly, one feels, because they were interrupted over the years for unrelated works). But these occasional disconnections, like the occasional disproportions, are small flaws in the large achievement of synchronizing scores of individual dramas with the sustained rhythms of two decades of personal and historical change.

1866–7 (Phineas Finn was in fact written between mid-November and mid-May of these years) was an appropriate moment to ponder change. The political world was stirring: the English Constitution, that peculiar compromise of elements, was reforming itself and this reform is the central political preoccupation of the novel. For prophets like Ruskin, Arnold and Carlyle popular agitation and extension of franchise threatened an ‘epoch of anarchy’. For others, Trollope among them, it was an age of improvement. For still others (Trollope was definitely not of their number) the millennium was promised. But all parties shared a common excitement that society was about to take a ‘leap in the dark’ or was ‘shooting Niagara’ as Carlyle put it, with an image which contrived to associate utter recklessness, abhorred American republicanism and absolute futility.

At this same time Trollope was considering important leaps of his own which he describes in language oddly reminiscent of that the politicians were currently using. ‘In 1867’ he writes ‘I made up my mind to take a step in life which was not unattended with peril, which many would call rash, and which, when taken, I should be sure at some period to regret. This step was the resignation of my place in the Post Office.’ Insofar as we can discern them his reasons for prematurely leaving a profession he had served with distinction were mixed: pique at missing a desired promotion, increasing commitment to journalism – and even his prodigious energies had flagged at being three hard-working men in one, editor, civil servant and novelist. But almost certainly he was partly moved by ambition, ‘the highest object of ambition to every educated Englishman’ he called it – that of going into parliament. In the mid sixties we see Trollope methodically girding himself for a parliamentary career, taking on work for no less than three political journals, writing a life of Palmerston, steeping himself in constitutional theory, following its practice from the visitors' gallery, and of course, introducing politics as a main ingredient in his fiction. Phineas Finn, the story of a tyro MP, may be taken as part of a general mobilization for this new career. But for any close consideration the novel must be more exactly adjusted to its historical and biographical backgrounds. First one notes that although its composition obviously coincides with the period of the second Reform Bill, it was nonetheless written at an awkward moment within that period. The interregnum between the Russell–Gladstone failed reform government of 1866 and the Derby–Disraeli aspirant but as yet unsuccessful reform government of 1867 was a difficult time to back political horses. Consequently the treatment in Phineas Finn of specific issues (notably the Reform Bill itself) is occasionally muffled or uncertain, and it is not fanciful to see a drift of mood in the novel as the Conservative triumph becomes more imminent. Secondly it is important to bear in mind that Phineas Finn was written at that optimistic time of life when Trollope could reasonably expect realization of his political hopes. As it turned out he was never to have the magic letters after his name. His parliamentary ambitions were squashed the next year (1868) when he stood as Liberal candidate for Beverley, an egregiously dirty borough, and came bottom of the poll in a contest so traumatically corrupt as to make electoral purity an idée fixe for the rest of his writing career. Disappointment as severe as this was bound to be consequential. After Phineas Finn the Palliser novels became the defeated candidate's soap-box; Trollope, frank as ever, admits it in his Autobiography: ‘As I was debarred from expressing my opinions in the House of Commons I took this method [the Palliser novels] of declaring myself.’ The angry word ‘debarred’, where a less aggrieved man would surely have used ‘unable’, suggests that even after twelve years Beverley rankled, and one does not have to weigh the niceties of words to find a corrosive chagrin in the novels of the early seventies. There are no sour grapes in Phineas Finn; unlike its immediate successors it is untainted by the disaster at Beverley, unlike them, although unillusioned about political life, it is in no damaging sense disillusioned.

II

It is tempting to recommend Phineas Finn by crying only what is fresh but Trollope had been writing hard for a quarter of a century and had come, it should be admitted, to rely on habit as much as invention in devising his fiction. It is no dispraise to him to say that, if repetitive, he is, at his best, a creatively repetitive novelist. In this respect his professional self-portrait – the industrious shoemaker turning out a variety of shoes on the same last – is more subtle than is generally understood. Phineas Finn has plenty of good Trollopian stock in it. There is, abundantly, the applauded ‘complete appreciation of the usual’. Less to modern taste is the customary front-of-stage love story (Trollope wrote only one novel without it and regarded that as a perverse experiment). The admirable style of the novel is that of the mature Trollope, purged of the facetious extravagance of his earlier comic mode; he would not in Phineas Finn describe married happiness as in Dr Thorne: ‘the sweet bliss of connubial reciprocity’. Instead we have language reduced to the ideal of polite invisibility he advocated to othe

rs: ‘I hold that gentleman to be best dressed whose dress no one observes. I am not sure but that the same may be said of an author's written language.’ Subdued the style may be, but we are nonetheless treated to the usual moral good sense in the author's very audible commentary on the action, a treat whose lavishness the modern reader may not always welcome. In plot Phineas Finn has the familiar mainspring of a Trollope novel, a serial dilemma of choice for the unheroic but well-intentioned hero, choice made complicated by conflicting interest, temptation, ambiguous situation and human weakness. Trollopian man lives in a perpetual quandary. As with all Trollope's fiction the matter of Phineas Finn can be abstracted at almost any point to a nagging question – ‘Can a man be honest in parliament and yet abandon all ideas of independence?’ ‘Whom should he marry?’ Even: ‘Can you forgive him?’ And underlying these is a layer of deeper moral uncertainty: ‘What is honesty, truth, goodness?’ ‘Is the world getting better or worse?’ ‘Should conduct be guided by prudence or feeling?’ The mood of Trollope's fiction is, typically, interrogative. This, one repeats, is no dispraise. The fundamental uncertainties are born not of authorial confusion but the recognized fact that, as a character in Phineas Finn remarks, ‘Life is so unlike theory.’ So unlike because although the notional ideals would have been familiar to Chaucer (Trollope's ‘trouthe’, ‘curtesie’ and ‘parfit gentleman’ are different mainly in the spelling), life in its modern forms has become intractable to traditional moral theory. This produces an ethical breakdown which Trollope identifies with a neat conundrum in an essay of 1867: ‘It is good to be honest and true. Yes indeed. There is no doubt of that. But what is truth and goodness?’ (No answer is forthcoming.) Practical examples of this kind of riddle can be found anywhere in the novel: what, for instance, is the honest thing to do when, as a man with strict views on electoral purity, Phineas is offered a rotten borough as his only chance of getting into the House? If he accepts he will be able to help purify the system, but he will have touched pitch; if he declines he will have preserved his personal honour but will be impotent to advance reform. Again no clear answer can be forthcoming. The man who would be honest is thus forced to feel his way inquisitively through every situation, testing, probing and more often than not making mistakes.

Doctor Thorne

Doctor Thorne Can You Forgive Her?

Can You Forgive Her? The Last Chronicle of Barset

The Last Chronicle of Barset The Fixed Period

The Fixed Period Phineas Redux

Phineas Redux The Way We Live Now

The Way We Live Now Castle Richmond

Castle Richmond The Bertrams

The Bertrams An Old Man's Love

An Old Man's Love The Belton Estate

The Belton Estate Marion Fay: A Novel

Marion Fay: A Novel The Claverings

The Claverings The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson

The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson Nina Balatka

Nina Balatka The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp

The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp Barchester Towers cob-2

Barchester Towers cob-2 The Chronicles of Barsetshire

The Chronicles of Barsetshire The Warden cob-1

The Warden cob-1 Framley Parsonage

Framley Parsonage Christmas at Thompson Hall

Christmas at Thompson Hall The Warden

The Warden The Palliser Novels

The Palliser Novels The Small House at Allington

The Small House at Allington Barchester Towers

Barchester Towers The Small House at Allington cob-5

The Small House at Allington cob-5 The Duke's Children

The Duke's Children Phineas Finn, the Irish Member

Phineas Finn, the Irish Member Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope