- Home

- Anthony Trollope

Framley Parsonage Page 8

Framley Parsonage Read online

Page 8

‘Robarts, my dear fellow,’ said Mr Sowerby, when they were well under way down one of the glades of the forest, – for the place where the hounds met was some four or five miles from the house of Chaldicotes, – ‘ride on with me a moment. I want to speak to you; and if I stay behind we shall never get to the hounds.’ So Mark, who had come expressly to escort the ladies, rode on alongside of Mr Sowerby in his pink coat.

‘My dear fellow, Fothergill tells me that you have some hesitation about going to Gatherum Castle.’

‘Well, I did decline, certainly. You know I am not a man of pleasure, as you are. I have some duties to attend to.’

‘Gammon!’ said Mr Sowerby; and as he said it he looked with a kind of derisive smile into the clergyman’s face.

‘It is easy enough to say that, Sowerby; and perhaps I have no right to expect that you should understand me.’

‘Ah, but I do understand you; and I say it is gammon. I would be the last man in the world to ridicule your scruples about duty, if this hesitation on your part arose from any such scruple. But answer me honestly, do you not know that such is not the case?’

‘I know nothing of the kind.’

‘Ah, but I think you do. If you persist in refusing this invitation will it not be because you are afraid of making Lady Lufton angry? I do not know what there can be in that woman that she is able to hold both you and Lufton in leading-strings.’

Robarts, of course, denied the charge and protested that he was not to be taken back to his own parsonage by any fear of Lady Lufton. But though he made such protest with warmth, he knew that he did so ineffectually. Sowerby only smiled and said that the proof of the pudding was in the eating.

‘What is the good of a man keeping a curate if it be not to save him from that sort of drudgery?’ he asked.

‘Drudgery! If I were a drudge how could I be here to-day?’

‘Well, Robarts, look here. I am speaking now, perhaps, with more of the energy of an old friend than circumstances fully warrant; but I am an older man than you, and as I have a regard for you I do not like to see you throw up a good game when it is in your hands.’

‘Oh, as far as that goes, Sowerby, I need hardly tell you that I appreciate your kindness.’

‘If you are content,’ continued the man of the world, ‘to live at Framley all your life, and to warm yourself in the sunshine of the dowager there, why, in such case, it may perhaps be useless for you to extend the circle of your friends; but if you have higher ideas than these, I think you will be very wrong to omit the present opportunity of going to the duke’s. I never knew the duke go so much out of his way to be civil to a clergyman as he has done in this instance.’

‘I am sure I am very much obliged to him.’

‘The fact is, that you may, if you please, make yourself popular in the county; but you cannot do it by obeying all Lady Lufton’s behests. She is a dear old woman, I am sure.’

‘She is, Sowerby; and you would say so, if you knew her.’

‘I don’t doubt it; but it would not do for you or me to live exactly according to her ideas. Now, here, in this case, the bishop of the diocese is to be one of the party, and he has, I believe, already expressed a wish that you should be another.’

‘He asked me if I were going.’

‘Exactly; and Archdeacon Grantly will be there.’

‘Will he?’ asked Mark. Now, that would be a great point gained, for Archdeacon Grantly was a close friend of Lady Lufton.

‘So I understand from Fothergill. Indeed, it will be very wrong of you not to go, and I tell you so plainly; and what is more, when you talk about your duty – you having a curate as you have – why, it is gammon.’ These last words he spoke looking back over his shoulder as he stood up in his stirrups, for he had caught the eye of the huntsman, who was surrounded by his hounds, and was now trotting on to join him.

During a great portion of the day, Mark found himself riding by the side of Mrs Proudie, as that lady leaned back in her carriage. And Mrs Proudie smiled on him graciously though her daughter would not do so. Mrs Proudie was fond of having an attendant clergyman; and as it was evident that Mr Robarts lived among nice people – titled dowagers, members of Parliament, and people of that sort – she was quite willing to install him as a sort of honorary chaplain pro tern.

‘I’ll tell you what we have settled, Mrs Harold Smith and I,’ said Mrs Proudie to him. ‘This lecture at Barchester will be so late on Saturday evening, that you had all better come and dine with us.’

Mark bowed and thanked her, and declared that he should be very happy to make one of such a party. Even Lady Lufton could not object to this, although she was not especially fond of Mrs Proudie.

‘And then they are to sleep at the hotel. It will really be too late for ladies to think of going back so far at this time of the year. I told Mrs Harold Smith, and Miss Dunstable too, that we could manage to make room at any rate for them. But they will not leave the other ladies; so they go to the hotel for that night. But, Mr Robarts, the bishop will never allow you to stay at the inn, so of course you will take a bed at the palace.’

It immediately occurred to Mark that as the lecture was to be given on Saturday evening, the next morning would be Sunday; and, on that Sunday, he would have to preach at Chaldicotes. ‘I thought they were all going to return the same night,’ said he.

‘Well, they did intend it; but you see Mrs Smith is afraid.’

‘I should have to get back here on the Sunday morning, Mrs Proudie.’

‘Ah, yes, that is bad – very bad, indeed. No one dislikes any interference with the Sabbath more than I do. Indeed, if I am particular about anything it is about that. But some works are works of necessity, Mr Robarts; are they not? Now you must necessarily be back at Chaldicotes on Sunday morning!’ And so the matter was settled. Mrs Proudie was very firm in general in the matter of Sabbath-day observances; but when she had to deal with such persons as Mrs Harold Smith, it was expedient that she should give way a little. ‘You can start as soon as it’s daylight, you know, if you like it, Mr Robarts,’ said Mrs Proudie.

There was not much to boast of as to the hunting, but it was a very pleasant day for the ladies. The men rode up and down the grass roads through the chase, sometimes in the greatest possible hurry as though they never could go quick enough; and then the coachmen would drive very fast also, though they did not know why, for a fast pace of movement is another of those contagious diseases. And then again the sportsmen would move at an undertaker’s pace, when the fox had traversed and the hounds would be at a loss to know which was the hunt and which was the heel; and then the carriage also would go slowly, and the ladies would stand up and talk. And then the time for lunch came; and altogether the day went by pleasantly enough.

‘And so that’s hunting, is it?’ said Miss Dunstable.

‘Yes, that’s hunting,’ said Mr Sowerby.

‘I did not see any gentleman do anything that I could not do myself, except there was one young man slipped off into the mud; and I shouldn’t like that.’

‘But there was no breaking of bones, was there, my dear?’ said Mrs Harold Smith.

‘And nobody caught any foxes,’ said Miss Dunstable. ‘The fact is, Mrs Smith, that I don’t think much more of their sport than I do of their business. I shall take to hunting a pack of hounds myself after this.’

‘Do, my dear, and I’ll be your whipper-in. I wonder whether Mrs Proudie would join us.’

‘I shall be writing to the duke to-night,’ said Mr Fothergill to Mark, as they were all riding up to the stable-yard together. ‘You will let me tell his grace that you will accept his invitation – will you not?’

‘Upon my word, the duke is very kind,’ said Mark.

‘He is very anxious to know you, I can assure you,’ said Fothergill.

What could a young flattered fool of a parson do, but say that he would go? Mark did say that he would go; and, in the course of the evening his friend Mr Sowerby congrat

ulated him, and the bishop joked with him and said that he knew that he would not give up good company so soon; and Miss Dunstable said she would make him her chaplain as soon as Parliament would allow quack doctors to have such articles – an allusion which Mark did not understand, till he learned that Miss Dunstable was herself the proprietress of the celebrated Oil of Lebanon, invented by her late respected father, and patented by him with such wonderful results in the way of accumulated fortune; and Mrs Proudie made him quite one of their party, talking to him about all manner of Church subjects; and then at last, even Miss Proudie smiled on him, when she learned that he had been thought worthy of a bed at a duke’s castle. And all the world seemed to be open to him.

But he could not make himself happy that evening. On the next morning he must write to his wife; and he could already see the look of painful sorrow which would fall upon his Fanny’s brow when she learned that her husband was going to be a guest at the Duke of Omnium’s. And he must tell her to send him money, and money was scarce. And then, as to Lady Lufton, should he send her some message, or should he not? In either case he must declare war against her. And then did he not owe everything to Lady Lufton? And thus in spite of all his triumphs he could not get himself to bed in a happy frame of mind.

On the next day, which was Friday, he postponed the disagreeable task of writing. Saturday would do as well; and on Saturday morning, before they all started for Barchester, he did write. And his letter ran as follows:-

‘Chaldicotes, – November, 185 — .

’DEAREST LOVE, – You will be astonished when I tell you how gay we all are here, and what further dissipations are in store for us. The Arabins, as you supposed, are not of our party; but the Proudies are, – as you supposed also. Your suppositions are always right. And what will you think when I tell you that I am to sleep at the palace on Saturday? You know that there is to be a lecture in Barchester on that day. Well; we must all go, of course, as Harold Smith, one of our set here, is to give it. And now it turns out that we cannot get back the same night because there is no moon; and Mrs Bishop would not allow that my cloth should be contaminated by an hotel; – very kind and considerate, is it not?

‘But I have a more astounding piece of news for you than this. There is to be a great party at Gatherum Castle next week, and they have talked me over into accepting an invitation which the duke sent expressly to me. I refused at first; but everybody here said that my doing so would be so strange; and then they all wanted to know my reason. When I came to render it, I did not know what reason I had to give. The bishop is going, and he thought it very odd that I should not go also, seeing that I was asked.

‘I know what my own darling will think, and I know that she will not be pleased, and I must put off my defence till I return to her from this ogre-land, – if ever I do get back alive. But joking apart, Fanny, I think that I should have been wrong to stand out, when so much was said about it. I should have been seeming to take upon myself to sit in judgment upon the duke. I doubt if there be a single clergyman in the diocese, under fifty years of age, who would have refused the invitation under such circumstances, – unless it be Crawley, who is so mad on the subject that he thinks it almost wrong to take a walk out of his own parish.

‘I must stay at Gatherum Castle over Sunday week – indeed, we only go there on Friday. I have written to Jones about the duties. I can make it up to him, as I know he wishes to go into Wales at Christmas. My wanderings will all be over then, and he may go for a couple of months if he pleases. I suppose you will take my classes in the school on Sunday, as well as your own; but pray make them have a good fire. If this is too much for you, make Mrs Podgens take the boys. Indeed I think that will be better.

‘Of course you will tell her ladyship of my whereabouts. Tell her from me, that as regards the bishop, as well as regarding another great personage, the colour has been laid on perhaps a little too thickly. Not that Lady Lufton would ever like him. Make her understand that my going to the duke’s has almost become a matter of conscience with me. I have not known how to make it appear that it would be right for me to refuse, without absolutely making a party matter of it. I saw that it would be said, that I, coming from Lady Lufton’s parish, could not go to the Duke of Omnium’s. This I did not choose.

‘I find that I shall want a little more money before I leave here, five or ten pounds – say ten pounds. If you cannot spare it, get it from Davis. He owes me more than that, a good deal.

‘And now, God bless and preserve you, my own love. Kiss my darling bairns for papa, and give them my blessing.

‘Always and ever your own,

‘M.R.’

And then there was written, on an outside scrap which was folded round the full-written sheet of paper, ‘Make it as smooth at Framley Court as possible.’

However strong, and reasonable, and unanswerable the body of Mark’s letter may have been, all his hesitation, weakness, doubt, and fear, were expressed in this short postscript.

CHAPTER 5

Amantium Irae Amoris Integratio1

AND now, with my reader’s consent, I will follow the postman with that letter to Framley; not by its own circuitous route indeed, or by the same mode of conveyance; for that letter went into Barchester by the Courcy night mail-cart, which, on its road, passes through the villages of Uffley and Chaldicotes, reaching Barchester in time for the up mail-train to London. By that train, the letter was sent towards the metropolis as far as the junction of the Barset branch line, but there it was turned in its course, and came down again by the main line as far as Silverbridge; at which place, between six and seven in the morning, it was shouldered by the Framley footpost messenger, and in due course delivered at the Framley Parsonage exactly as Mrs Robarts had finished reading prayers to the four servants. Or, I should say rather, that such would in its usual course have been that letter’s destiny. As it was, however, it reached Silverbridge on Sunday, and lay there till the Monday, as the Framley people have declined their Sunday post. And then again, when the letter was delivered at the parsonage, on that wet Monday morning, Mrs Robarts was not at home. As we are all aware, she was staying with her ladyship at Framley Court.

‘Oh, but it’s mortial wet,’ said the shivering postman as he handed in that and the vicar’s newspaper. The vicar was a man of the world, and took the Jupiter.

‘Come in, Robin postman, and warm theeself awhile,’ said Jemima the cook, pushing a stool a little to one side, but still well in front of the big kitchen fire.

‘Well, I dudna jist know how it’ll be. The wery ‘edges ’ as eyes and tells on me in Silverbridge, if I so much as stops to pick a blackberry.’

‘There bain’t no hedges here, mon, nor yet no blackberries; so sit thee down and warm theeself. That’s better nor blackberries I’m thinking,’ and she handed him a bowl of tea with a slice of buttered toast.

Robin postman took the proffered tea, put his dripping hat on the ground, and thanked Jemima cook. ‘But I dudna jist know how it’ll be,’ said he; ‘only it do pour so tarnation heavy.’ Which among us, O my readers, could have withstood that temptation?

Such was the circuitous course of Mark’s letter; but as it left Chaldicotes on Saturday evening, and reached Mrs Robarts on the following morning, or would have done, but for that intervening Sunday, doing all its peregrinations during the night, it may be held that its course of transport was not inconveniently arranged. We, however, will travel by a much shorter route.

Robin, in the course of his daily travels, passed, first the post-office at Framley, then the Framley Court back entrance, and then the vicar’s house, so that on this wet morning Jemima cook was not able to make use of his services in transporting this letter back to her mistress; for Robin had another village before him, expectant of its letters.

‘Why didn’t thee leave it, mon, with Mr Applejohn at the Court?’ Mr Applejohn was the butler who took the letter-bag. ‘Thee know’st as how missus was there.’

And then Rob

in, mindful of the tea and toast, explained to her courteously how the law made it imperative on him to bring the letter to the very house that was indicated, let the owner of the letter be where she might; and he laid down the law very satisfactorily with sundry long-worded quotations. Not to much effect, however, for the housemaid called him an oaf; and Robin would decidedly have had the worst of it had not the gardener come in and taken his part. ‘They women knows nothin’, and understands nothin’,’ said the gardener. ‘Give us hold of the letter. I’ll take it up to the house. It’s the master’s fist.’ And then Robin postman went on one way, and the gardener, he went the other. The gardener never disliked an excuse for going up to the Court gardens, even on so wet a day as this.

Mrs Robarts was sitting over the drawing-room fire with Lady Meredith, when her husband’s letter was brought to her. The Framley Court letter-bag had been discussed at breakfast; but that was now nearly an hour since, and Lady Lufton, as was her wont, was away in her own room writing her own letters, and looking after her own matters: for Lady Lufton was a person who dealt in figures herself, and understood business almost as well as Harold Smith. And on that morning she also had received a letter which had displeased her not a little. Whence arose this displeasure neither Mrs Robarts nor Lady Meredith knew; but her ladyship’s brow had grown black at breakfast-time; she had bundled up an ominous-looking epistle into her bag without speaking of it, and had left the room immediately that breakfast was over.

‘There’s something wrong,’ said Sir George.

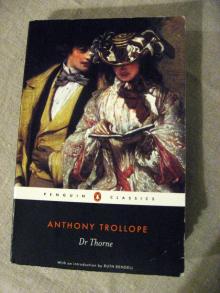

Doctor Thorne

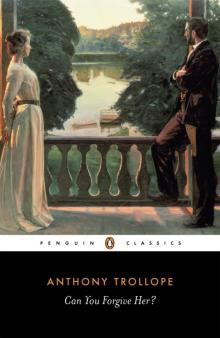

Doctor Thorne Can You Forgive Her?

Can You Forgive Her? The Last Chronicle of Barset

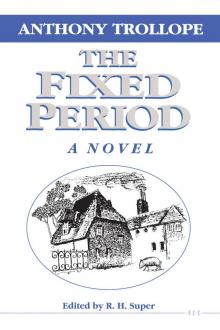

The Last Chronicle of Barset The Fixed Period

The Fixed Period Phineas Redux

Phineas Redux The Way We Live Now

The Way We Live Now Castle Richmond

Castle Richmond The Bertrams

The Bertrams An Old Man's Love

An Old Man's Love The Belton Estate

The Belton Estate Marion Fay: A Novel

Marion Fay: A Novel The Claverings

The Claverings The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson

The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson Nina Balatka

Nina Balatka The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp

The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp Barchester Towers cob-2

Barchester Towers cob-2 The Chronicles of Barsetshire

The Chronicles of Barsetshire The Warden cob-1

The Warden cob-1 Framley Parsonage

Framley Parsonage Christmas at Thompson Hall

Christmas at Thompson Hall The Warden

The Warden The Palliser Novels

The Palliser Novels The Small House at Allington

The Small House at Allington Barchester Towers

Barchester Towers The Small House at Allington cob-5

The Small House at Allington cob-5 The Duke's Children

The Duke's Children Phineas Finn, the Irish Member

Phineas Finn, the Irish Member Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope