- Home

- Anthony Trollope

The Palliser Novels Page 6

The Palliser Novels Read online

Page 6

“I’ll make your money all straight,” said George.

“Indeed you’ll do nothing of the kind,” said Kate. “I’m ruined, but you are ruineder. But what signifies? It is such a great thing ever to have had six weeks’ happiness, that the ruin is, in point of fact, a good speculation. What do you say, Alice? Won’t you vote, too, that we’ve done it well?”

“I think we’ve done it very well. I have enjoyed myself thoroughly.”

“And now you’ve got to go home to John Grey and Cambridgeshire! It’s no wonder you should be melancholy.” That was the thought in Kate’s mind, but she did not speak it out on this occasion.

“That’s good of you, Alice,” said Kate. “Is it not, George? I like a person who will give a hearty meed of approbation.”

“But I am giving the meed of approbation to myself.”

“I like a person even to do that heartily,” said Kate. “Not that George and I are thankful for the compliment. We are prepared to admit that we owe almost everything to you, — are we not, George?”

“I’m not; by any means,” said George.

“Well, I am, and I expect to have something pretty said to me in return. Have I been cross once, Alice?”

“No; I don’t think you have. You are never cross, though you are often ferocious.”

“But I haven’t been once ferocious, — nor has George.”

“He would have been the most ungrateful man alive if he had,” said Alice. “We’ve done nothing since we’ve started but realize from him that picture in ‘Punch’ of the young gentleman at Jeddo who had a dozen ladies to wait upon him.”

“And now he has got to go home to his lodgings, and wait upon himself again. Poor fellow! I do pity you, George.”

“No, you don’t; — nor does Alice. I believe girls always think that a bachelor in London has the happiest of all lives. It’s because they think so that they generally want to put an end to the man’s condition.”

“It’s envy that makes us want to get married, — not love,” said Kate.

“It’s the devil in some shape, as often as not,” said he. “With a man, marriage always seems to him to be an evil at the instant.”

“Not always,” said Alice.

“Almost always; — but he does it, as he takes physic, because something worse will come if he don’t. A man never likes having his tooth pulled out, but all men do have their teeth pulled out, — and they who delay it too long suffer the very mischief.”

“I do like George’s philosophy,” said Kate, getting up from her chair as she spoke; “it is so sharp, and has such a pleasant acid taste about it; and then we all know that it means nothing. Alice, I’m going up-stairs to begin the final packing.”

“I’ll come with you, dear.”

“No, don’t. To tell the truth I’m only going into that man’s room because he won’t put up a single thing of his own decently. We’ll do ours, of course, when we go up to bed. Whatever you disarrange to-night, Master George, you must rearrange for yourself to-morrow morning, for I promise I won’t go into your room at five o’clock.”

“How I do hate that early work,” said George.

“I’ll be down again very soon,” said Kate. “Then we’ll take one turn on the bridge and go to bed.”

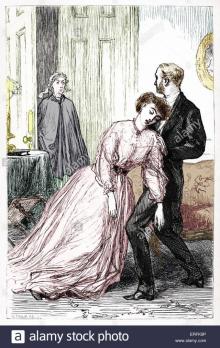

Alice and George were left together sitting in the balcony. They had been alone together before many times since their travels had commenced; but they both of them felt that there was something to them in the present moment different from any other period of their journey. There was something that each felt to be sweet, undefinable, and dangerous. Alice had known that it would be better for her to go up-stairs with Kate; but Kate’s answer had been of such a nature that had she gone she would have shown that she had some special reason for going. Why should she show such a need? Or why, indeed, should she entertain it?

Alice was seated quite at the end of the gallery, and Kate’s chair was at her feet in the corner. When Alice and Kate had seated themselves, the waiter had brought a small table for the coffee-cups, and George had placed his chair on the other side of that. So that Alice was, as it were, a prisoner. She could not slip away without some special preparation for going, and Kate had so placed her chair in leaving, that she must actually have asked George to move it before she could escape. But why should she wish to escape? Nothing could be more lovely and enticing than the scene before her. The night had come on, with quick but still unperceived approach, as it does in those parts; for the twilight there is not prolonged as it is with us more northern folk. The night had come on, but there was a rising moon, which just sufficed to give a sheen to the water beneath her. The air was deliciously soft; — of that softness which produces no sensation either of warmth or cold, but which just seems to touch one with loving tenderness, as though the unseen spirits of the air kissed one’s forehead as they passed on their wings. The Rhine was running at her feet, so near, that in the soft half light it seemed as though she might step into its ripple. The Rhine was running by with that delicious sound of rapidly moving waters, that fresh refreshing gurgle of the river, which is so delicious to the ear at all times. If you be talking, it wraps up your speech, keeping it for yourselves, making it difficult neither to her who listens nor to him who speaks. If you would sleep, it is of all lullabies the sweetest. If you are alone and would think, it aids all your thoughts. If you are alone, and, alas! would not think, — if thinking be too painful, — it will dispel your sorrow, and give the comfort which music alone can give. Alice felt that the air kissed her, that the river sang for her its sweetest song, that the moon shone for her with its softest light, — that light which lends the poetry of half-developed beauty to everything that it touches. Why should she leave it?

Nothing was said for some minutes after Kate’s departure, and Alice was beginning to shake from her that half feeling of danger which had come over her. Vavasor had sat back in his chair, leaning against the house, with his feet raised upon a stool; his arms were folded across his breast, and he seemed to have divided himself between his thoughts and his cigar. Alice was looking full upon the river, and her thoughts had strayed away to her future home among John Grey’s flower-beds and shrubs; but the river, though it sang to her pleasantly, seemed to sing a song of other things than such a home as that, — a song full of mystery, as are all river songs when one tries to understand their words.

“When are you to be married, Alice?” said George at last.

“Oh, George!” said she. “You ask me a question as though you were putting a pistol to my ear.”

“I’m sorry the question was so unpleasant.”

“I didn’t say that it was unpleasant; but you asked it so suddenly! The truth is, I didn’t expect you to speak at all just then. I suppose I was thinking of something.”

“But if it be not unpleasant, — when are you to be married?”

“I do not know. It is not fixed.”

“But about when, I mean? This summer?”

“Certainly not this summer, for the summer will be over when we reach home.”

“This winter? Next spring? Next year? — or in ten years’ time?”

“Before the expiration of the ten years, I suppose. Anything more exact than that I can’t say.”

“I suppose you like it?” he then said.

“What, being married? You see I’ve never tried yet.”

“The idea of it, — the anticipation, You look forward with satisfaction to the kind of life you will lead at Nethercoats? Don’t suppose I am saying anything against it, for I have no conception what sort of a place Nethercoats is. On the whole I don’t know that there is any kind of life better than that of an English country gentleman in his own place; — that is, if he can keep it up, and not live as the old squire does, in a state of chronic poverty.”

“Mr Grey’s place doesn’t entitle him to be called a country gentleman.”

“But you like the prospect of it?”

“Oh, George, how you do cr

oss-question one! Of course I like it, or I shouldn’t have accepted it.”

“That does not follow. But I quite acknowledge that I have no right to cross-question you. If I ever had such right on the score of cousinship, I have lost it on the score of — ; but we won’t mind that, will we, Alice?” To this she at first made no answer, but he repeated the question. “Will we, Alice?”

“Will we what?”

“Recur to the old days.”

“Why should we recur to them? They are passed, and as we are again friends and dear cousins the sting of them is gone.”

“Ah, yes! The sting of them is gone. It is for that reason, because it is so, that we may at last recur to them without danger. If we regret nothing, — if neither of us has anything to regret, why not recur to them, and talk of them freely?”

“No, George; that would not do.”

“By heavens, no! It would drive me mad; and if I know aught of you, it would hardly leave you as calm as you are at present.”

“As I would wish to be left calm — “

“Would you? Then I suppose I ought to hold my tongue. But, Alice, I shall never have the power of speaking to you again as I speak now. Since we have been out together, we have been dear friends; is it not so?”

“And shall we not always be dear friends?”

“No, certainly not. How will it be possible? Think of it. How can I really be your friend when you are the mistress of that man’s house in Cambridgeshire?”

“George!”

“I mean nothing disrespectful. I truly beg your pardon if it has seemed so. Let me say that gentleman’s house; — for he is a gentleman.”

“That he certainly is.”

“You could not have accepted him were he not so. But how can I be your friend when you are his wife? I may still call you cousin Alice, and pat your children on the head if I chance to see them; and shall stop in the streets and shake hands with him if I meet him; — that is if my untoward fate does not induce him to cut my acquaintance; — but as for friendship, that will be over when you and I shall have parted next Thursday evening at London Bridge.”

“Oh, George, don’t say so!”

“But I do.”

“And why on Thursday? Do you mean that you won’t come to Queen Anne Street any more?”

“Yes, that is what I do mean. This trip of ours has been very successful, Kate says. Perhaps Kate knows nothing about it.”

“It has been very pleasant, — at least to me.”

“And the pleasure has had no drawback?”

“None to me.”

“It has been very pleasant to me, also; — but the pleasure has had its alloy. Alice, I have nothing to ask from you, — nothing.”

“Anything that you should ask, I would do for you.”

“I have nothing to ask; — nothing. But I have one word to say.”

“George, do not say it. Let me go up-stairs. Let me go to Kate.”

“Certainly; if you wish it you shall go.” He still held his foot against the chair which barred her passage, and did not attempt to rise as he must have done to make way for her passage out. “Certainly you shall go to Kate, if you refuse to hear me. But after all that has passed between us, after these six weeks of intimate companionship, I think you ought to listen to me. I tell you that I have nothing to ask. I am not going to make love to you.”

Alice had commenced some attempt to rise, but she had again settled herself in her chair. And now, when he paused for a moment, she made no further sign that she wished to escape, nor did she say a word to intimate her further wish that he should be silent.

“I am not going to make love to you,” he said again. “As for making love, as the word goes, that must be over between you and me. It has been made and marred, and cannot be remade. It may exist, or it may have been expelled; but where it does not exist, it will never be brought back again.”

“It should not be spoken of between you and me.”

“So, no doubt, any proper-going duenna would say, and so, too, little children should be told; but between you and me there can be no necessity for falsehood. We have grown beyond our sugar-toothed ages, and are now men and women. I perfectly understood your breaking away from me. I understood you, and in spite of my sorrow knew that you were right. I am not going to accuse or to defend myself; but I knew that you were right.”

“Then let there be no more about it.”

“Yes; there must be more about it. I did not understand you when you accepted Mr Grey. Against him I have not a whisper to make. He may be perfect for aught I know. But, knowing you as I thought I did, I could not understand your loving such a man as him. It was as though one who had lived on brandy should take himself suddenly to a milk diet, — and enjoy the change! A milk diet is no doubt the best. But men who have lived on brandy can’t make those changes very suddenly. They perish in the attempt.”

“Not always, George.”

“It may be done with months of agony; — but there was no such agony with you.”

“Who can tell?”

“But you will tell me the cure was made. I thought so, and therefore thought that I should find you changed. I thought that you, who had been all fire, would now have turned yourself into soft-flowing milk and honey, and have become fit for the life in store for you. With such a one I might have travelled from Moscow to Malta without danger. The woman fit to be John Grey’s wife would certainly do me no harm, — could not touch my happiness. I might have loved her once, — might still love the memory of what she had been; but her, in her new form, after her new birth, — such a one as that, Alice, could be nothing to me. Don’t mistake me. I have enough of wisdom in me to know how much better, ay, and happier a woman she might be. It was not that I thought you had descended in the scale; but I gave you credit for virtues which you have not acquired. Alice, that wholesome diet of which I spoke is not your diet. You would starve on it, and perish.”

He had spoken with great energy, but still in a low voice, having turned full round upon the table, with both his arms upon it, and his face stretched out far over towards her. She was looking full at him; and, as I have said before, that scar and his gloomy eyes and thick eyebrows seemed to make up the whole of his face. But the scar had never been ugly to her. She knew the story, and when he was her lover she had taken pride in the mark of the wound. She looked at him, but though he paused she did not speak. The music of the river was still in her ears, and there came upon her a struggle as though she were striving to understand its song. Were the waters also telling her of the mistake she had made in accepting Mr Grey as her husband? What her cousin was now telling her, — was it not a repetition of words which she had spoken to herself hundreds of times during the last two months? Was she not telling herself daily, — hourly, — always, — in every thought of her life, that in accepting Mr Grey she had assumed herself to be mistress of virtues which she did not possess? Had she not, in truth, rioted upon brandy, till the innocence of milk was unfitted for her? This man now came and rudely told her all this, — but did he not tell her the truth? She sat silent and convicted; only gazing into his face when his speech was done.

“I have learned this since we have been again together, Alice; and finding you, not the angel I had supposed, finding you to be the same woman I had once loved, — the safety that I anticipated has not fallen to my lot. That’s all. Here’s Kate, and now we’ll go for our walk.”

CHAPTER VI

The Bridge over the Rhine

“George,” said Kate, speaking before she quite got up to them, “will you tell me whether you have been preparing all your things for an open sale by auction?” Then she stole a look at Alice, and having learned from that glance that something had occurred which prevented Alice from joining her in her raillery, she went on with it herself rapidly, as though to cover Alice’s confusion, and give her time to rally before they should all move. “Would you believe it? he had three razors laid out on his table — “

&nb

sp; “A man must shave, — even at Basle.”

“But not with three razors at once; and three hair-brushes, and half a dozen toothbrushes, and a small collection of combs, and four or five little glass bottles, looking as though they contained poison, — all with silver tops. I can only suppose you desired to startle the weak mind of the chambermaid. I have put them all up; but remember this, if they are taken out again you are responsible. And I will not put up your boots, George. What can you have wanted with three pairs of boots at Basle?”

“When you have completed the list of my wardrobe we’ll go out upon the bridge. That is, if Alice likes it.”

“Oh, yes; I shall like it.”

“Come along then,” said Kate. And so they moved away. When they got upon the bridge Alice and Kate were together, while George strolled behind them, close to them, but not taking any part in their conversation, — as though he had merely gone with them as an escort. Kate seemed to be perfectly content with this arrangement, chattering to Alice, so that she might show that there was nothing serious on the minds of any of them. It need hardly be said that Alice at this time made no appeal to George to join them. He followed them at their heels, with his hands behind his back, looking down upon the pavement and simply waiting upon their pleasure.

“Do you know,” said Kate, “I have a very great mind to run away.”

“Where do you want to run to?”

“Well; — that wouldn’t much signify. Perhaps I’d go to the little inn at Handek. It’s a lonely place, where nobody would hear of me, — and I should have the waterfall. I’m afraid they’d want to have their bill paid. That would be the worst of it.”

“But why run away just now?”

“I won’t, because you wouldn’t like going home with George alone, — and I suppose he’d be bound to look after me, as he’s doing now. I wonder what he thinks of having to walk over the bridge after us girls. I suppose he’d be in that place down there drinking beer, if we weren’t here.”

“If he wanted to go, I dare say he would, in spite of us.”

Doctor Thorne

Doctor Thorne Can You Forgive Her?

Can You Forgive Her? The Last Chronicle of Barset

The Last Chronicle of Barset The Fixed Period

The Fixed Period Phineas Redux

Phineas Redux The Way We Live Now

The Way We Live Now Castle Richmond

Castle Richmond The Bertrams

The Bertrams An Old Man's Love

An Old Man's Love The Belton Estate

The Belton Estate Marion Fay: A Novel

Marion Fay: A Novel The Claverings

The Claverings The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson

The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson Nina Balatka

Nina Balatka The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp

The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp Barchester Towers cob-2

Barchester Towers cob-2 The Chronicles of Barsetshire

The Chronicles of Barsetshire The Warden cob-1

The Warden cob-1 Framley Parsonage

Framley Parsonage Christmas at Thompson Hall

Christmas at Thompson Hall The Warden

The Warden The Palliser Novels

The Palliser Novels The Small House at Allington

The Small House at Allington Barchester Towers

Barchester Towers The Small House at Allington cob-5

The Small House at Allington cob-5 The Duke's Children

The Duke's Children Phineas Finn, the Irish Member

Phineas Finn, the Irish Member Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope