- Home

- Anthony Trollope

Phineas Finn, the Irish Member Page 20

Phineas Finn, the Irish Member Read online

Page 20

‘A hundred pounds.’

‘If it be inconvenient, sir, I can do without it.’ He had not as yet paid for his gun, or for that velvet coat in which he had been shooting, or, most probably, for the knickerbockers. He knew he wanted the hundred pounds badly; but he felt ashamed of himself in asking for it. If he were once in office, – though the office were but a sorry junior lordship, – he would repay his father instantly.

‘You shall have it, of course,’ said the doctor; ‘but do not let the necessity for asking for more hundreds come oftener than you can help.’ Phineas said that he would not, and then there was no further discourse about money. It need hardly be said that he told his father nothing of that bill which he had endorsed for Laurence Fitzgibbon.

At last came the time which called him again to London and the glories of London life, – to lobbies, and the clubs, and the gossip of men in office, and the chance of promotion for himself; to the glare of the gas-lamps, the mock anger of rival debaters, and the prospect of the Speaker's wig. During the idleness of the recess he had resolved at any rate upon this, – that a month of the session should not have passed by before he had been seen upon his legs in the House, – had been seen and heard. And many a time as he had wandered alone, with his gun, across the bogs which lie on the other side of the Shannon from Killaloe, he had practised the sort of address which he would make to the House. He would be short, – always short; and he would eschew all action and gesticulation; Mr Monk had been very urgent in his instructions to him on that head; but he would be especially careful that no words should escape him which had not in them some purpose. He might be wrong in his purpose, but purpose there should be. He had been twitted more than once at Killaloe with his silence; – for it had been conceived by his fellow-townsmen that he had been sent to Parliament on the special ground of his eloquence. They should twit him no more on his next return. He would speak and would carry the House with him if a human effort might prevail.

So he packed up his things, and started again for London in the beginning of February. ‘Good-bye, Mary,’ he said, with his sweetest smile. But on this occasion there was no kiss, and no culling of locks. ‘I know he cannot help it,’ said Mary to herself. ‘It is his position. But whether it be for good or evil, I will be true to him.’

‘I am afraid you are unhappy,’ Barbara Finn said to her on the next morning.

‘No; I am not unhappy, – not at all. I have a great deal to make me happy and proud. I don't mean to be a bit unhappy.’ Then she turned away and cried heartily, and Barbara Finn cried with her for company.

CHAPTER 17

Phineas Finn Returns to London

PHINEAS had received two letters during his recess at Killaloe from two women who admired him much, which, as they were both short, shall be submitted to the reader. The first was as follows:—

Saulsby, October 20, 186—

MY DEAR MR FINN,

I write a line to tell you that our marriage is to be hurried on as quickly as possible. Mr Kennedy does not like to be absent from Parliament; nor will he be content to postpone the ceremony till the session be over. The day fixed is the 3rd of December, and we then go at once to Rome, and intend to be back in London by the opening of Parliament.

Yours most sincerely,

LAURA STANDISH.

Our London address will be No. 52, Grosvenor Place.

To this he wrote an answer as short, expressing his ardent wishes that those winter hymeneals might produce nothing but happiness, and saying that he would not be in town many days before he knocked at the door of No 52, Grosvenor Place.

And the second letter was as follows: —

Great Marlborough Street, December, 186—

DEAR AND HONOURED SIR,

Bunce is getting ever so anxious about the rooms, and says as how he has a young Equity draftsman and wife and baby as would take the whole house, and all because Miss Pouncefoot said a word about her port wine, which any lady of her age might say in her tantrums, and mean nothing after all. Me and Miss Pouncefoot's knowed each other for seven years, and what's a word or two as isn't meant after that? But, honoured sir, it's not about that as I write to trouble you, but to ask if I may say for certain that you'll take the rooms again in February. It's easy to let them for the month after Christmas, because of the pantomimes. Only say at once, because Bunce is nagging me day after day. I don't want nobody's wife and baby to have to do for, and 'd sooner have a Parliament gent like yourself than any one else.

Yours umbly and respectful,

Jane Bunce.

To this he replied that he would certainly come back to the rooms in Great Marlborough Street, should he be lucky enough to find them vacant, and he expressed his willingness to take them on and from the 1st of February. And on the 3rd of February he found himself in the old quarters, Mrs Bunce having contrived, with much conjugal adroitness, both to keep Miss Pouncefoot and to stave off the Equity draftsman's wife and baby. Bunce, however, received Phineas very coldly, and told his wife the same evening that as far as he could see their lodger would never turn up to be a trump in the matter of the ballot. ‘If he means well, why did he go and stay with them lords down in Scotland? I knows all about it. I knows a man when I sees him. Mr Low, who's looking out to be a Tory judge some of these days, is a deal better; – because he knows what he's after.’

Immediately on his return to town, Phineas found himself summoned to a political meeting at Mr Mildmay's house in St James's Square. ‘We're going to begin in earnest this time,’ Barrington Erle said to him at the club.

‘I am glad of that,’ said Phineas.

‘I suppose you heard all about it down at Loughlinter?’

Now, in truth, Phineas had heard very little of any settled plan down at Loughlinter. He had played a game of chess with Mr Gresham, and had shot a stag with Mr Palliser, and had discussed sheep with Lord Brentford, but had hardly heard a word about politics from any one of those influential gentlemen. From Mr Monk he had heard much of a coming Reform Bill; but his communications with Mr Monk had rather been private discussions, – in which he had learned Mr Monk's own views on certain points, – than revelations on the intention of the party to which Mr Monk belonged. ‘I heard of nothing settled,’ said Phineas; ‘but I suppose we are to have a Reform Bill.’

‘That is a matter of course.’

‘And I suppose we are not to touch the question of ballot.’31

‘That's the difficulty,’ said Barrington Erle. ‘But of course we shan't touch it as long as Mr Mildmay is in the Cabinet. He will never consent to the ballot as First Minister of the Crown.’

‘Nor would Gresham, or Palliser,’ said Phineas, who did not choose to bring forward his greatest gun at first.

‘I don't know about Gresham. It is impossible to say what Gresham might bring himself to do. Gresham is a man who may go any lengths before he has done. Planty Pall,’ – for such was the name by which Mr Plantagenet Palliser was ordinarily known among his friends, – ‘would of course go with Mr Mildmay and the Duke.’

‘And Monk is opposed to the ballot,’ said Phineas.

‘Ah, that's the question. No doubt he has assented to the proposition of a measure without the ballot; but if there should come a row, and men like Turnbull demand it, and the London mob kick up a shindy, I don't know how far Monk would be steady.’

‘Whatever he says, he'll stick to.’

‘He is your leader, then?’ asked Barrington.

‘I don't know that I have a leader. Mr Mildmay leads our side; and if anybody leads me, he does. But I have great faith in Mr Monk.’

‘There's one who would go for the ballot to-morrow, if it were brought forward stoutly,’ said Barrington Erle to Mr Ratler a few minutes afterwards, pointing to Phineas as he spoke.

‘I don't think much of that young man,’ said Ratler.

Mr Bonteen and Mr Ratler had put their heads together during that last evening at Loughlinter, and had agreed that they did not think much of Phineas

Finn. Why did Mr Kennedy go down off the mountain to get him a pony? And why did Mr Gresham play chess with him? Mr Ratler and Mr Bonteen may have been right in making up their minds to think but little of Phineas Finn, but Barrington Erle had been quite wrong when he had said that Phineas would go for the ballot to-morrow. Phineas had made up his mind very strongly that he would always oppose the ballot. That he would hold the same opinion throughout his life, no one should pretend to say; but in his present mood, and under the tuition which he had received from Mr Monk, he was prepared to demonstrate, out of the House and in it, that the ballot was, as a political measure, unmanly, ineffective, and enervating. Enervating had been a great word with Mr Monk, and Phineas had clung to it with admiration.

The meeting took place at Mr Mildmay's on the third day of the session. Phineas had of course heard of such meetings before, but had never attended one. Indeed, there had been no such gathering when Mr Mildmay's party came into power early in the last session. Mr Mildmay and his men had then made their effort in turning out their opponents, and had been well pleased to rest awhile upon their oars. Now, however, they must go again to work, and therefore the liberal party was collected at Mr Mild-may's house, in order that the liberal party might be told what it was that Mr Mildmay and his Cabinet intended to do.

Phineas Finn was quite in the dark as to what would be the nature of the performance on this occasion, and entertained some idea that every gentleman present would be called upon to express individually his assent or dissent in regard to the measure proposed. He walked to St James's Square with Laurence Fitzgibbon; but even with Fitzgibbon was ashamed to show his ignorance by asking questions. ‘After all,’ said Fitzgibbon, ‘this kind of thing means nothing. I know as well as possible, and so do you, what Mr Mildmay will say, – and then Gresham will say a few words; and then Turnbull will make a murmur, and then we shall all assent, – to anything or to nothing; – and then it will be over.’ Still Phineas did not understand whether the assent required would or would not be an individual personal assent. When the affair was over he found that he was disappointed, and that he might almost as well have stayed away from the meeting, – except that he had attended at Mr Mildmay's bidding, and had given a silent adhesion to Mr Mildmay's plan of reform for that session. Laurence Fitzgibbon had been very nearly correct in his description of what would occur. Mr Mildmay made a long speech. Mr Turnbull, the great Radical of the day, – the man who was supposed to represent what many called the Manchester school of politics, – asked half a dozen questions. In answer to these Mr Gresham made a short speech. Then Mr Mildmay made another speech, and then all was over. The gist of the whole thing was, that there should be a Reform Bill, – very generous in its enlargement of the franchise, – but no ballot. Mr Turnbull expressed his doubt whether this would be satisfactory to the country; but even Mr Turnbull was soft in his tone and complaisant in his manner. As there was no reporter present, that plan of turning private meetings at gentlemen's houses into public assemblies not having been as yet adopted, – there could be no need for energy or violence. They went to Mr Mildmay's house to hear Mr Mildmay's plan, – and they heard it.

Two days after this Phineas was to dine with Mr Monk. Mr Monk had asked him in the lobby of the House. ‘I don't give dinner parties,’ he said, ‘but I should like you to come and meet Mr Turnbull.’ Phineas accepted the invitation as a matter of course. There were many who said that Mr Turnbull was the greatest man in the nation, and that the nation could be saved only by a direct obedience to Mr Turnbull's instructions. Others said that Mr Turnbull was a demagogue, and at heart a rebel; that he was un-English, false, and very dangerous. Phineas was rather inclined to believe the latter statement; and as danger and dangerous men are always more attractive than safety and safe men, he was glad to have an opportunity of meeting Mr Turnbull at dinner.

In the meantime he went to call on Lady Laura, whom he had not seen since the last evening which he spent in her company at Loughlinter, – whom, when he was last speaking to her, he had kissed close beneath the falls of the Linter. He found her at home, and with her was her husband. ‘Here is a Darby and Joan meeting, is it not?’ she said, getting up to welcome him. He had seen Mr Kennedy before, and had been standing close to him during the meeting at Mr Mildmay's.

‘I am very glad to find you both together.’

‘But Robert is going away this instant,’ said Lady Laura. ‘Has he told you of our adventures at Rome?’

‘Not a word.’

‘Then I must tell you; – but not now. The dear old Pope was so civil to us. I came to think it quite a pity that he should be in trouble.’32

‘I must be off,’ said the husband, getting up. ‘But I shall meet you at dinner, I believe.’

‘Do you dine at Mr Monk's?’

‘Yes, and am asked expressly to hear Turnbull make a convert of you. There are only to be us four. Au revoir.’ Then Mr Kennedy went, and Phineas found himself alone with Lady Laura. He hardly knew how to address her, and remained silent. He had not prepared himself for the interview as he ought to have done, and felt himself to be awkward. She evidently expected him to speak, and for a few seconds sat waiting for what he might say.

At last she found that it was incumbent on her to begin. ‘Were you surprised at our suddenness when you got my note?’

‘A little. You had spoken of waiting.’

‘I had never imagined that he would have been impetuous. And he seems to think that even the business of getting himself married would not justify him in staying away from Parliament. He is a rigid martinet in all matters of duty.’

‘I did not wonder that he should be in a hurry, but that you should submit.’

‘I told you that I should do just what the wise people told me. I asked papa, and he said that it would be better. So the lawyers were driven out of their minds, and the milliners out of their bodies, and the thing was done.’

‘Who was there at the marriage?’

‘Oswald was not there. That I know is what you mean to ask. Papa said that he might come if he pleased. Oswald stipulated that he should be received as a son. Then my father spoke the hardest word that ever fell from his mouth.’

‘What did he say?’

‘I will not repeat it, – not altogether. But he said that Oswald was not entitled to a son's treatment. He was very sore about my money, because Robert was so generous as to his settlement. So the breach between them is as wide as ever.’

‘And where is Chiltern now?’ said Phineas.

‘Down in Northamptonshire, staying at some inn from whence he hunts. He tells me that he is quite alone, – that he never dines out, never has any one to dine with him, that he hunts five or six days a week, – and reads at night.’

‘That is not a bad sort of life.’

‘Not if the reading is any good. But I cannot bear that he should be so solitary. And if he breaks down in it, then his companions will not be fit for him. Do you ever hunt?’

‘Oh yes, – at home in county Clare. All Irishmen hunt.’

‘I wish you would go down to him and see him. He would be delighted to have you.’

Phineas thought over the proposition before he answered it, and then made the reply that he had made once before. ‘I would do so, Lady Laura, – but that I have no money for hunting in England.’

‘Alas, alas!’ said she, smiling. ‘How that hits one on every side!’

‘I might manage it, – for a couple of days, – in March.’

‘Do not do what you think you ought not to do,’ said Lady Laura.

‘No; – certainly. But I should like it, and if I can I will.’

‘He could mount you, I have no doubt. He has no other expense now, and keeps a stable full of horses. I think he has seven or eight. And now tell me, Mr Finn; when are you going to charm the House? Or is it your first intention to strike terror?’

He blushed, – he knew that he blushed as he answered. ‘Oh, I suppose I shall make some sort of

attempt before long. I can't bear the idea of being a bore.’

‘I think you ought to speak, Mr Finn.’

‘I do not know about that, but I certainly mean to try. There will be lots of opportunities about the new Reform Bill. Of course you know that Mr Mildmay is going to bring it in at once. You hear all that from Mr Kennedy.’

‘And papa has told me. I still see papa almost every day. You must call upon him. Mind you do.’ Phineas said that he certainly would. ‘Papa is very lonely now, and I sometimes feel that I have been almost cruel in deserting him. And I think that he has a horror of the house, – especially later in the year, – always fancying that he will meet Oswald. I am so unhappy about it all, Mr Finn.’

‘Why doesn't your brother marry?’ said Phineas, knowing nothing as yet of Lord Chiltern and Violet Effingham. ‘If he were to marry well, that would bring your father round.’

‘Yes, – it would.’

‘And why should he not?’

Lady Laura paused before she answered; and then she told the whole story. ‘He is violently in love, and the girl he loves has refused him twice.’

‘Is it with Miss Effingham?’ asked Phineas, guessing the truth at once, and remembering what Miss Effingham had said to him when riding in the wood.

‘Yes; – with Violet Effingham; my father's pet, his favourite, whom he loves next to myself, – almost as well as myself; whom he would really welcome as a daughter. He would gladly make her mistress of his house, and of Saulsby. Everything would then go smoothly.’

‘But she does not like Lord Chiltern?’

‘I believe she loves him in her heart; but she is afraid of him. As she says herself, a girl is bound to be so careful of herself. With all her seeming frolic, Violet Effingham is very wise.’

Phineas, though not conscious of any feeling akin to jealousy, was annoyed at the revelation made to him. Since he had heard that Lord Chiltern was in love with Miss Effingham, he did not like Lord Chiltern quite as well as he had done before. He himself had simply admired Miss Effingham, and had taken pleasure in her society; but, though this had been all, he did not like to hear of another man wanting to marry her, and he was almost angry with Lady Laura for saying that she believed Miss Effingham loved her brother. If Miss Effingham had twice refused Lord Chiltern, that ought to have been sufficient. It was not that Phineas was in love with Miss Effingham himself. As he was still violently in love with Lady Laura, any other love was of course impossible; but, nevertheless, there was something offensive to him in the story as it had been told. ‘If it be wisdom on her part,’ said he, answering Lady Laura's last words, ‘you cannot find fault with her for her decision.’

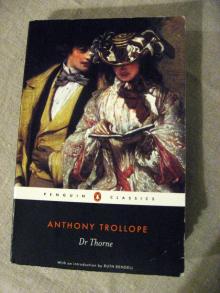

Doctor Thorne

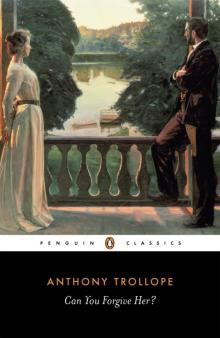

Doctor Thorne Can You Forgive Her?

Can You Forgive Her? The Last Chronicle of Barset

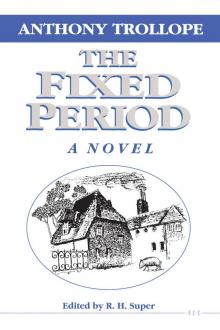

The Last Chronicle of Barset The Fixed Period

The Fixed Period Phineas Redux

Phineas Redux The Way We Live Now

The Way We Live Now Castle Richmond

Castle Richmond The Bertrams

The Bertrams An Old Man's Love

An Old Man's Love The Belton Estate

The Belton Estate Marion Fay: A Novel

Marion Fay: A Novel The Claverings

The Claverings The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson

The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson Nina Balatka

Nina Balatka The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp

The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp Barchester Towers cob-2

Barchester Towers cob-2 The Chronicles of Barsetshire

The Chronicles of Barsetshire The Warden cob-1

The Warden cob-1 Framley Parsonage

Framley Parsonage Christmas at Thompson Hall

Christmas at Thompson Hall The Warden

The Warden The Palliser Novels

The Palliser Novels The Small House at Allington

The Small House at Allington Barchester Towers

Barchester Towers The Small House at Allington cob-5

The Small House at Allington cob-5 The Duke's Children

The Duke's Children Phineas Finn, the Irish Member

Phineas Finn, the Irish Member Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope