- Home

- Anthony Trollope

An Old Man's Love Page 19

An Old Man's Love Read online

Page 19

CHAPTER XIX.

MR WHITTLESTAFF'S JOURNEY DISCUSSED.

"I don't think that if I were you I would go up to London, MrWhittlestaff," said Mary. This was on the Tuesday morning.

"Why not?"

"I don't think I would."

"Why should you interfere?"

"I know I ought not to interfere."

"I don't think you ought. Especially as I have taken the trouble toconceal what I am going about."

"I can guess," said Mary.

"You ought not to guess in such a matter. You ought not to have it onyour mind at all. I told you that I would not tell you. I shall go.That's all that I have got to say."

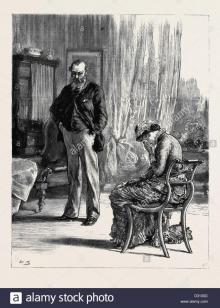

The words with which he spoke were ill-natured and savage. The readerwill find them to be so, if he thinks of them. They were such thata father would hardly speak, under any circumstances, to a grown-updaughter,--much less that a lover would address to his mistress. AndMary was at present filling both capacities. She had been taken intohis house almost as an adopted daughter, and had, since that time,had all the privileges accorded to her. She had now been promotedstill higher, and had become his affianced bride. That the man shouldhave turned upon her thus, in answer to her counsel, was savage, orat least ungracious. But at every word her heart became fuller andmore full of an affection as for something almost divine. What otherman had ever shown such love for any woman? and this love was shownto her,--who was nothing to him,--who ate the bread of charity in hishouse. And it amounted to this, that he intended to give her up toanother man,--he who had given such proof of his love,--he, of whomshe knew that this was a question of almost life and death,--becausein looking into his face she had met there the truth of his heart!Since that first avowal, made before Gordon had come,--made at amoment when some such avowal from her was necessary,--she had spokenno word as to John Gordon. She had endeavoured to show no sign. Shehad given herself up to her elder lover, and had endeavoured tohave it understood that she had not intended to transfer herselfbecause the other man had come across her path again like a flash oflightning. She had dined in company with her younger lover withoutexchanging a word with him. She had not allowed her eyes to fall uponhim more than she could help, lest some expression of tendernessshould be seen there. Not a word of hope had fallen from her lipswhen they had first met, because she had given herself to another.She was sure of herself in that. No doubt there had come moments inwhich she had hoped--nay, almost expected--that the elder of the twomight give her up; and when she had felt sure that it was not to beso, her very soul had rebelled against him. But as she had takentime to think of it, she had absolved him, and had turned her angeragainst herself. Whatever he wanted,--that she believed it would beher duty to do for him, as far as its achievement might be in herpower.

She came round and put her arm upon him, and looked into his face."Don't go to London. I ask you not to go."

"Why should I not go?"

"To oblige me. You pretend to have a secret, and refuse to say whyyou are going. Of course I know."

"I have written a letter to say that I am coming."

"It is still lying on the hall-table down-stairs. It will not go tothe post till you have decided."

"Who has dared to stop it?"

"I have. I have dared to stop it. I shall dare to put it in the fireand burn it. Don't go! He is entitled to nothing. You are entitledto have,--whatever it is that you may want, though it is but such atrifle."

"A trifle, Mary!"

"Yes. A woman has a little gleam of prettiness about her,--thoughhere it is but of a common order."

"Anything so uncommon I never came near before."

"Let that pass; whether common or uncommon, it matters nothing. It issomething soft, which will soon pass away, and of itself can do nogood. It is contemptible."

"You are just Mrs Baggett over again."

"Very well; I am quite satisfied. Mrs Baggett is a good woman. Shecan do something beyond lying on a sofa and reading novels, while hergood looks fade away. It is simply because a woman is pretty and weakthat she is made so much of, and is encouraged to neglect her duties.By God's help I will not neglect mine. Do not go to London."

He seemed as though he hesitated as he sat there under the spellof her little hand upon his shoulder. And in truth he did hesitate.Could it not be that he should be allowed to sit there all his days,and have her hand about his neck somewhat after this fashion? Washe bound to give it all up? What was it that ordinary selfishnessallowed? What depth of self-indulgence amounted to a wickedness whicha man could not permit himself to enjoy without absolutely hatinghimself? It would be easy in this case to have all that he wanted. Heneed not send the letter. He need not take this wretched journey toLondon. Looking forward, as he thought that he could look, judgingfrom the girl's character, he believed that he would have all that hedesired,--all that a gracious God could give him,--if he would makeher the recognised partner of his bed and his board. Then would he beproud when men should see what sort of a wife he had got for himselfat last in place of Catherine Bailey. And why should she not lovehim? Did not all her words tend to show that there was love?

And then suddenly there came a frown across his face, as she stoodlooking at him. She was getting to know the manner of that frown. Nowshe stooped down to kiss it away from his brow. It was a brave thingto do; but she did it with a consciousness of her courage. "Now I mayburn the letter," she said, as though she were about to depart uponthe errand.

"No, by heaven!" he said. "Let me have a sandwich and a glass ofwine, for I shall start in an hour."

With a glance of his thoughts he had answered all those questions.He had taught himself what ordinary selfishness allowed. Ordinaryselfishness,--such selfishness as that of which he would havepermitted himself the indulgence,--must have allowed him to disregardthe misery of John Gordon, and to keep the girl to himself. Asfar as John Gordon was concerned, he would not have cared for hissufferings. He was as much to himself,--or more,--than could beJohn Gordon. He did not love John Gordon, and could have doomed himto tearing his hair,--not without regret, but at any rate withoutremorse. He had settled that question. But with Mary Lawrie theremust be a never-dying pang of self-accusation, were he to take herto his arms while her love was settled elsewhere. It was not that hefeared her for himself, but that he feared himself for her sake. Godhad filled his heart with love of the girl,--and, if it was love,could it be that he would destroy her future for the gratificationof his own feelings? "I tell you it is no good," he said, as shecrouched down beside him, almost sitting on his knee.

At this moment Mrs Baggett came into the room, detecting Mary almostin the embrace of her old master. "He's come back again, sir," saidMrs Baggett.

"Who has come back?"

"The Sergeant."

"Then you may tell him to go about his business. He is not wanted, atany rate. You are to remain here, and have your own way, like an oldfool."

"I am that, sir."

"There is not any one coming to interfere with you."

"Sir!"

Then Mary got up, and stood sobbing at the open window. "At any rate,you'll have to remain here to look after the house, even if I goaway. Where is the Sergeant?"

"He's in the stable again."

"What! drunk?"

"Well, no; he's not drunk. I think his wooden leg is affected soonerthan if he had two like mine, or yours, sir. And he did manage to goin of his self, now that he knows the way. He's there among the hay,and I do think it's very unkind of Hayonotes to say as he'll spoilit. But how am I to get him out, unless I goes away with him?"

"Let him stay there and give him some dinner. I don't know what elseyou've to do."

"He can't stay always,--in course, sir. As Hayonotes says,--what's heto do with a wooden-legged sergeant in his stable as a permanence? Ihad come to say I was to go home with him."

"You're to do nothing of the kind."

"What is it you mean, then, about my taking care of the house?"

"Never you

mind. When I want you to know, I shall tell you." ThenMrs Baggett bobbed her head three times in the direction of MaryLawrie's back, as though to ask some question whether the leaving thehouse might not be in reference to Mary's marriage. But she fearedthat it was not made in reference to Mr Whittlestaff's marriagealso. What had her master meant when he had said that there was noone coming to interfere with her, Mrs Baggett? "You needn't ask anyquestions just at present, Mrs Baggett," he said.

"You don't mean as you are going up to London just to give her up tothat young fellow?"

"I am going about my own business, and I won't be inquired into,"said Mr Whittlestaff.

"Then you're going to do what no man ought to do."

"You are an impertinent old woman," said her master.

"I daresay I am. All the same, it's my duty to tell you my mind. Youcan't eat me, Mr Whittlestaff, and it wouldn't much matter if youcould. When you've said that you'll do a thing, you ought not to goback for any other man, let him be who it may,--especially not inrespect of a female. It's weak, and nobody wouldn't think a straw ofyou for doing it. It's some idea of being generous that you have gotinto your head. There ain't no real generosity in it. I say it ain'tmanly, and that's what a man ought to be."

Mary, though she was standing at the window, pretending to look outof it, knew that during the whole of this conversation Mrs Baggettwas making signs at her,--as though indicating an opinion that shewas the person in fault. It was as though Mrs Baggett had said thatit was for her sake,--to do something to gratify her,--that MrWhittlestaff was about to go to London. She knew that she at anyrate was not to blame. She was struggling for the same end as MrsBaggett, and did deserve better treatment. "You oughtn't to bothergoing up to London, sir, on any such errand, and so I tells you, MrWhittlestaff," said Mrs Baggett.

"I have told him the same thing myself," said Mary Lawrie, turninground.

"If you told him as though you meant it, he wouldn't go," said MrsBaggett.

"That's all you know about it," said Mr Whittlestaff. "Now the factis, I won't stand this kind of thing. If you mean to remain here, youmust be less free with your tongue."

"I don't mean to remain here, Mr Whittlestaff. It's just that as I'mcoming to. There's Timothy Baggett is down there among the hosses,and he says as I am to go with him. So I've come up here to saythat if he's allowed to sleep it off to-day, I'll be ready to startto-morrow."

"I tell you I am not going to make any change at all," said MrWhittlestaff.

"You was saying you was going away,--for the honeymoon, I didsuppose."

"A man may go away if he pleases, without any reason of that kind.Oh dear, oh dear, that letter is not gone! I insist that that lettershould go. I suppose I must see about it myself." Then when hebegan to move, the women moved also. Mary went to look after thesandwiches, and Mrs Baggett to despatch the letter. In ten minutesthe letter was gone, and half an hour afterwards Mr Whittlestaff hadhimself driven down to the station.

"What is it he means, Miss?" said Mrs Baggett, when the master wasgone.

"I do not know," said Mary, who was in truth very angry with the oldwoman.

"He wants to make you Mrs Whittlestaff."

"In whatever he wants I shall obey him,--if I only knew how."

"It's what you is bound to do, Miss Mary. Think of what he has donefor you."

"I require no one to tell me that."

"What did Mr Gordon come here for, disturbing everybody? Nobodyasked him;--at least, I suppose nobody asked him." There was aninsinuation in this which Mary found it hard to bear. But it wasbetter to bear it than to argue on such a point with the servant."And he said things which put the master about terribly."

"It was not my doing."

"But he's a man as needn't have his own way. Why should Mr Gordonhave everything just as he likes it? I never heard tell of Mr Gordontill he came here the other day. I don't think so much of Mr Gordonmyself." To this Mary, of course, made no answer. "He's no businessdisturbing people when he's not sent for. I can't abide to see MrWhittlestaff put about in this way. I have known him longer than youhave."

"No doubt."

"He's a man that'll be driven pretty nigh out of his mind if he'sdisappointed." Then there was silence, as Mary was determined not todiscuss the matter any further. "If you come to that, you needn'tmarry no one unless you pleases." Mary was still silent. "Theyshouldn't make me marry them unless I was that way minded. I can'tabide such doings," the old woman again went on after a pause. "Iknows what I knows, and I sees what I sees."

"What do you know?" said Mary, driven beyond her powers of silence.

"The meaning is, that Mr Whittlestaff is to be disappointed afterhe have received a promise. Didn't he have a promise?" To this MrsBaggett got no reply, though she waited for one before she went onwith her argument. "You knows he had; and a promise between a ladyand gentleman ought to be as good as the law of the land. You standthere as dumb as grim death, and won't say a word, and yet it alldepends upon you. Why is it to go about among everybody, that he'snot to get a wife just because a man's come home with his pocketsfull of diamonds? It's that that people'll say; and they'll say thatyou went back from your word just because of a few precious stones.I wouldn't like to have it said of me anyhow."

This was very hard to bear, but Mary found herself compelled tobear it. She had determined not to be led into an argument with MrsBaggett on the subject, feeling that even to discuss her conductwould be an impropriety. She was strong in her own conduct, and knewhow utterly at variance it had been with all that this woman imputedto her. The glitter of the diamonds had been merely thrown in by MrsBaggett in her passion. Mary did not think that any one would be sobase as to believe such an accusation as that. It would be said ofher that her own young lover had come back suddenly, and that she hadpreferred him to the gentleman to whom she was tied by so many bonds.It would be said that she had given herself to him and had then takenback the gift, because the young lover had come across her path. Andit would be told also that there had been no word of promise given tothis young lover. All that would be very bad, without any allusionto a wealth of diamonds. It would not be said that, before she hadpledged herself to Mr Whittlestaff, she had pleaded her affectionfor her young lover, when she had known nothing even of his presentexistence. It would not be known that though there had been nolover's vows between her and John Gordon, there had yet been on bothsides that unspoken love which could not have been strengthened byany vows. Against all that she must guard herself, without thinkingof the diamonds. She had endeavoured to guard herself, and she hadthought also of the contentment of the man who had been so good toher. She had declared to herself that of herself she would think notat all. And she had determined also that all the likings,--nay, theaffection of John Gordon himself,--should weigh not at all with her.She had to decide between the two men, and she had decided that bothhonesty and gratitude required her to comply with the wishes of theelder. She had done all that she could with that object, and was ither fault that Mr Whittlestaff had read the secret of her heart, andhad determined to give way before it? This had so touched her that itmight almost be said that she knew not to which of her two suitorsher heart belonged. All this, if stated in answer to Mrs Baggett'saccusations, would certainly exonerate herself from the stigma thrownupon her, but to Mrs Baggett she could not repeat the explanation.

"It nigh drives me wild," said Mrs Baggett. "I don't suppose youever heard of Catherine Bailey?"

"Never."

"And I ain't a-going to tell you. It's a romance as shall be wrappedinside my own bosom. It was quite a tragedy,--was Catherine Bailey;and one as would stir your heart up if you was to hear it. CatherineBailey was a young woman. But I'm not going to tell you thestory;--only that she was no more fit for Mr Whittlestaff than anyof them stupid young girls that walks about the streets gaping in atthe shop-windows in Alresford. I do you the justice, Miss Lawrie, tosay as you are such a female as he ought to look after."

"Thank you, Mrs Baggett

."

"But she led him into such trouble, because his heart is soft, aswas dreadful to look at. He is one of them as always wants a wife.Why didn't he get one before? you'll say. Because till you came inthe way he was always thinking of Catherine Bailey. Mrs Compas shebecome. 'Drat her and her babies!' I often said to myself. What wasCompas? No more than an Old Bailey lawyer;--not fit to be looked atalongside of our Mr Whittlestaff. No more ain't Mr John Gordon, tomy thinking. You think of all that, Miss Mary, and make up your mindwhether you'll break his heart after giving a promise. Heart-breakingain't to him what it is to John Gordon and the likes of him."

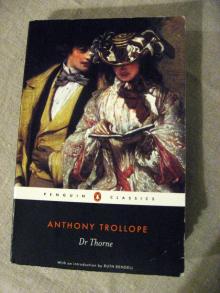

Doctor Thorne

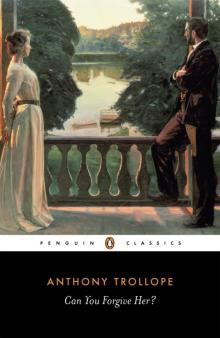

Doctor Thorne Can You Forgive Her?

Can You Forgive Her? The Last Chronicle of Barset

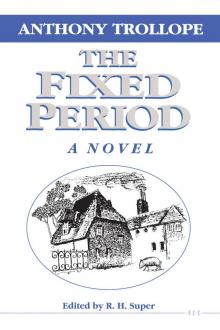

The Last Chronicle of Barset The Fixed Period

The Fixed Period Phineas Redux

Phineas Redux The Way We Live Now

The Way We Live Now Castle Richmond

Castle Richmond The Bertrams

The Bertrams An Old Man's Love

An Old Man's Love The Belton Estate

The Belton Estate Marion Fay: A Novel

Marion Fay: A Novel The Claverings

The Claverings The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson

The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson Nina Balatka

Nina Balatka The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp

The Relics of General Chasse: A Tale of Antwerp Barchester Towers cob-2

Barchester Towers cob-2 The Chronicles of Barsetshire

The Chronicles of Barsetshire The Warden cob-1

The Warden cob-1 Framley Parsonage

Framley Parsonage Christmas at Thompson Hall

Christmas at Thompson Hall The Warden

The Warden The Palliser Novels

The Palliser Novels The Small House at Allington

The Small House at Allington Barchester Towers

Barchester Towers The Small House at Allington cob-5

The Small House at Allington cob-5 The Duke's Children

The Duke's Children Phineas Finn, the Irish Member

Phineas Finn, the Irish Member Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope